From the earliest moments in the history of virtual reality (VR), the United States military forces have been a driving factor in developing and applying new VR technologies. Along with the entertainment industry, the military is responsible for the most dramatic evolutionary leaps in the VR field. In this article, we'll look at how the military uses virtual reality for most everything -- from learning to fly a jet fighter to putting out a fire on board a ship.

Virtual environments work well in military applications. When well designed, they provide the user with an accurate simulation of real events in a safe, controlled environment. Specialized military training can be very expensive, particularly for vehicle pilots. Some training procedures have an element of danger when using real situations. While the initial development of VR gear and software is expensive, in the long run it's much more cost effective than putting soldiers into real vehicles or physically simulated situations. VR technology also has other potential applications that can make military activities safer.

Advertisement

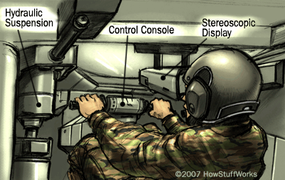

That's why when engineers first began to experiment with head-mounted displays (HMD), the military took notice. Both the Navy and the Air Force funded some of the earliest work in developing effective HMDs. The first HMDs weren't linked to a virtual environment -- they were linked to a camera. Engineers mounted a camera to a servo-controlled base (a base platform connected to one or more motors that adjust the position of the base by rotating or tilting the platform).

A user wearing the HMD could control where the camera pointed by turning his head in different directions. In an early application of this technique, Bell Helicopter Company mounted an infrared camera on the bottom of a helicopter. The chopper pilot could get an unprecedented look at the terrain beneath his vehicle when flying at night, making it safer to land in difficult conditions.

Today, the military uses VR techniques not only for training and safety enhancement, but also to analyze military maneuvers and battlefield positions. In the next section, we'll look at the various simulators commonly used in military training.

Advertisement