In Donora, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) by car south of Pittsburgh along the Monongahela River, what used to be a Chinese restaurant is now the home of the Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum.

Over the years, scholars from academic institutions all over the world have made their way to the humble local volunteer-run institution to peruse its archive of documents, blueprints, microfilm, scientific studies and film footage, according to volunteer curator and researcher Brian Charlton, who notes with amusement that he also doubles as the janitor. "I was just mopping before I returned your call," he explains one recent Saturday morning.

Advertisement

There's continuing interest in the museum's collection because it documents one of the worst pollution catastrophes in U.S. history, a toxic smog that enveloped Donora in late October 1948 and killed more than 20 residents, in addition to sickening thousands more. Many credit the disaster with awakening the American public to the dangers of air pollution, and stirring an outcry that eventually led to enactment of the first federal clean air laws in the 1950s and 1960s.

In the words of a historical study published in April 2018 in the American Journal of Public Health, Donora's killer smog "changed the face of environmental protection in the United States."

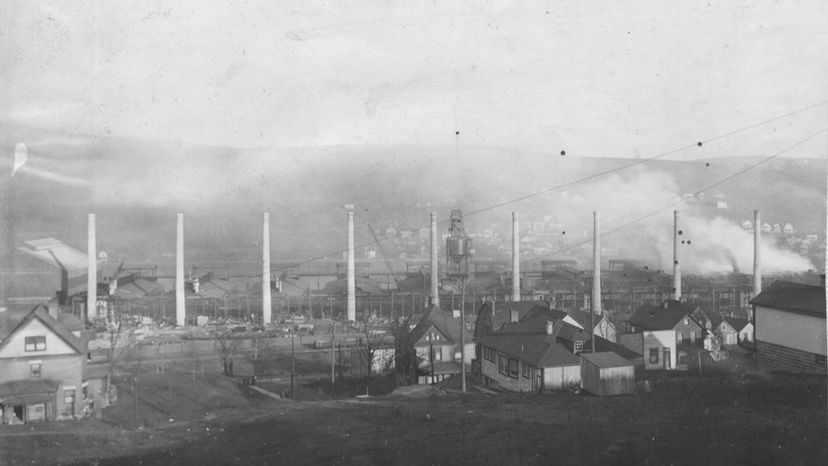

Today, Donora is an out-of-the-way town of just 4,000 inhabitants, without even a gas station or a grocery store, But back in 1948, Charlton explains, it was several times larger, a bustling center of industry that was home to both a zinc works with 10 smelters and a steel mill that used the zinc to galvanize its products. While the zinc works provided thousands of residents with good-paying jobs, there was a major downside. Workers were paid a full day's wage for just a few hours of work, because too much exposure to the zinc could make them ill. "The layman's term was the zinc shakes," Charlton explains.

The plant also continuously released billowing emissions into the local sky, laden with a soup of pollutants that included "hydrogen fluoride, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, multiple sulfur compounds, and heavy metals within fine particulate matter," according to the AJPH study.

In the neighboring village of Webster, the pollution from Donora had a devastating effect on local farmers' orchards. "It just destroyed their way of life," Charlton says. In Donora, the pollution killed vegetation, denuding hillsides and causing so much erosion that a local cemetery became an unusable wasteland of rocks and dirt.

Advertisement