Modern Fingerprinting Techniques

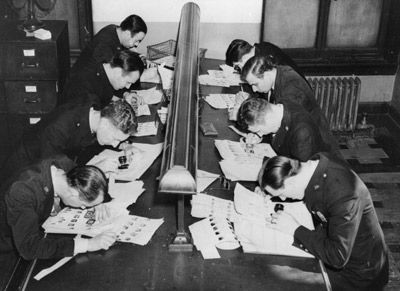

The Henry system finally enabled law enforcement officials to classify and identify individual fingerprints. Unfortunately, the system was very cumbersome. When fingerprints came in, detectives would have to compare them manually with the fingerprints on file for a specific criminal (that's if the person even had a record). The process would take hours or even days and didn't always produce a match. By the 1970s, computers were in existence, and the FBI knew it had to automate the process of classifying, searching for and matching fingerprints. The Japanese National Police Agency paved the way for this automation, establishing the first electronic fingerprint matching system in the 1980s. Their Automated Fingerprint Identification Systems (AFIS), eventually enabled law enforcement officials around the world to cross-check a print with millions of fingerprint records almost instantaneously.

AFIS collects digital fingerprints with sensors. Computer software then looks for patterns and minutiae points (based on Sir Edward Henry's system) to find the best match in its database.

Advertisement

The first AFIS system in the U.S. was

speedier than previous manual systems. However, there was no coordination between different agencies. Because many local, state and federal law enforcement departments weren't connected to the same AFIS system, they couldn't share information. That meant that if a man was arrested in Phoenix, Ariz. and his prints were on file at a police station in Duluth, Minn., there might have been no way for the Arizona police officers to find the fingerprint record.

That changed in 1999, with the introduction of Integrated AFIS (IAFIS). This system is maintained by the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services Division. It can categorize, search and retrieve fingerprints from virtually anywhere in the country in as little as 30 minutes. It also includes mug shots and criminal histories on some 47 million people. IAFIS allows local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to have access to the same huge database of information. The IAFIS system operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But IAFIS isn't just used for criminal checks. It also collects fingerprints for employment, licenses and social services programs (such as homeless shelters). When all of these uses are taken together, about one out of every six people in this country has a fingerprint record on IAFIS.

Despite the modern technologies, fingerprinting is still an old detective's trick. What are some other ways to catch a thief? Find out in the next section.