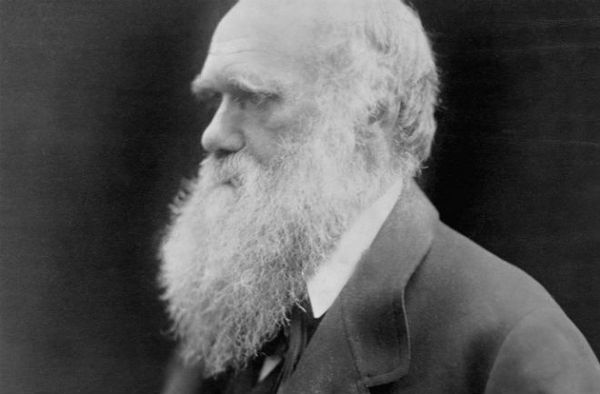

Galton's career can be divided into two parts: his early life as an explorer, travel writer and scientific innovator; and then his later obsession with eugenics following the release of "On the Origin of Species."

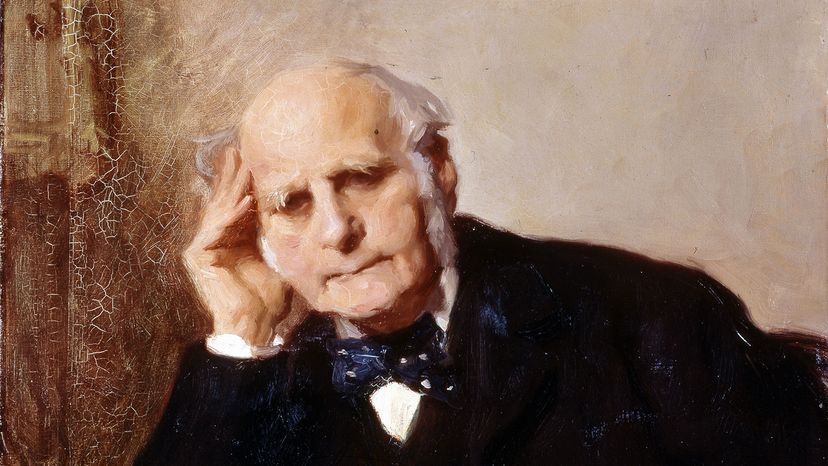

Galton was born in 1822 and was considered to be a child prodigy. Soon after he graduated from university, his father died, leaving him the family fortune inherited from an industrialist grandfather. Free from the tyranny of earning a living, young Galton indulged his passion for travel and hunting, going on expeditions to Egypt and the Holy Land. Galton's cousin Darwin got him an introduction to the Royal Geographical Society, where he hatched a monthslong expedition to map unexplored corners Africa.

During his African journeys, Galton showed a real talent for the detailed measurements of mapmaking, hinting at the patient dedication to data collection would serve him well throughout his career. He proved less successful, however, at international diplomacy. After attempting to win passage through a tribal king's land by presenting him with cheap gifts, Galton returned to his tent to find the king's own peace offering, a nude young woman smeared in butter and ochre dye.

Galton had her "ejected with scant ceremony," as he put it, less for moral reasons than a concern about staining his white linen suit. Galton wrote that she was "as capable of leaving a mark on anything she touched as a well-inked printer's roller." The king, needless to say, told Galton to scram.

Back in London, Galton wrote a popular account of his African travels as well as how-to guides for would-be adventurers. Then he began to indulge his scientific curiosity on all manner of subjects still in their scientific infancy.

First was a fascination with meteorology. If you think today's weather forecasts are bad, imagine how awful they were in the 1850s when The Times of London began publishing the first predictions of tomorrow's weather. Galton approached the problem like he would dozens of others in his career: He went out and collected data.

In 1861, he set up a system by which meteorologists across Europe collected weather data — temperature, wind speed and direction, barometric pressure — three times a day at the exact same hours for a month. Galton then analyzed the data for recognizable patterns of cause and effect, and in the process discovered the phenomenon known as an "anticyclone."

But perhaps Galton's greatest contribution to weather forecasting was inventing some of the first weather maps that included wind speed arrows, temperature discs, and simple symbols for rain and sunshine.

Even some of Galton's notable early failures became wild successes. In 1864, he and some fellow Victorian notables launched a weekly scientific journal called The Reader, which disbanded after two years. Some other colleagues revived the journal a few years later under the name Nature, now one of the world's most respected scientific publications.