Some plants -- the angiosperms -- evolved to take the pollination process a step further. In terms of species, angiosperms are the most prolific type; many trees and shrubs, along with all manner of fruits, vegetables, grains, cacti, and wildflowers are considered angiosperms [source: Raven]. These are the flowering plants, and not only do they produce seeds, they also flower and produce protective fruits. These reproductive safety nets are also better at luring mobile organisms to assist them in completing their life cycle.

So let's look at how this works in your typical flower. Pollen grains are created through the process of meiosis, during which cells divide and grow in number. The grains of pollen are often located in pollen sacs on the ends of the stamen (the male parts of the flower), which typically surround the carpel (the female parts of the flower). The stamen generally come in two sections: the two-lobed anther, which house the pollen sacks, and the filament, the stalk on which the anther perch.

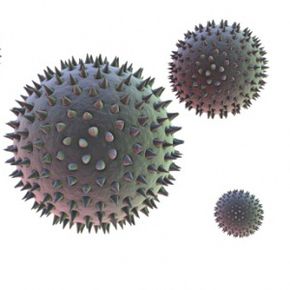

Each grain gradually develops a tough outer wall to shelter it during its journey. Once it's deposited at its destination, grains of pollen settle on a flower's stigma -- the entrance to the ovary. Like with the gymnosperms, germination and pollen-tube formation follow fertilization, but this time both sperm are used. While one fertilizes the egg cell, the other is tasked with fertilizing another cell that will develop into the endosperm, which is what growing plant embryos consume before and during the sprouting process.

Different flowers grow in different configurations, and while the majority of angiosperms carry both stamen and carpal components, some do not. For those species, male and female reproductive cells can be found on different flowers of the same plant -- similar to how many gymnosperms' pinecones are commonly configured. Or, in some cases, each particular plant specimen may feature only one or the other, varying the process slightly.