If you're a farmers market regular, you might be familiar with the groundcherry, a small husked berry that resembles a tiny yellow tomatillo, but tastes like fruity mix of pineapple, cherry tomato and vanilla. Chances are that if you've sampled groundcherries — also called "husk cherries," "strawberry tomatoes" and "pineapple tomatillos" — the farmer only had a small supply on hand. That's because the plants, native to Central and South America, are notoriously unfriendly to growers.

Groundcherries earned their name because their sprawling, tomato-like vines grow close to the soil in tangled bushes and the husked fruit falls to the ground at peak ripeness. Harvesting must be done by hand and fruit left on the ground in the rain quickly rots. A perfectly ripe groundcherry is a flavorful delight, but the labor and losses make it an unprofitable crop for farmers.

Advertisement

Groundcherries are one of hundreds of so-called "orphan crops" — fruits, vegetables and grains that are grown in small-scale, often subsistence farms around the world, but have largely been ignored by commercial growers because of poor yields and low resistance to pests and bad weather. But that might be changing.

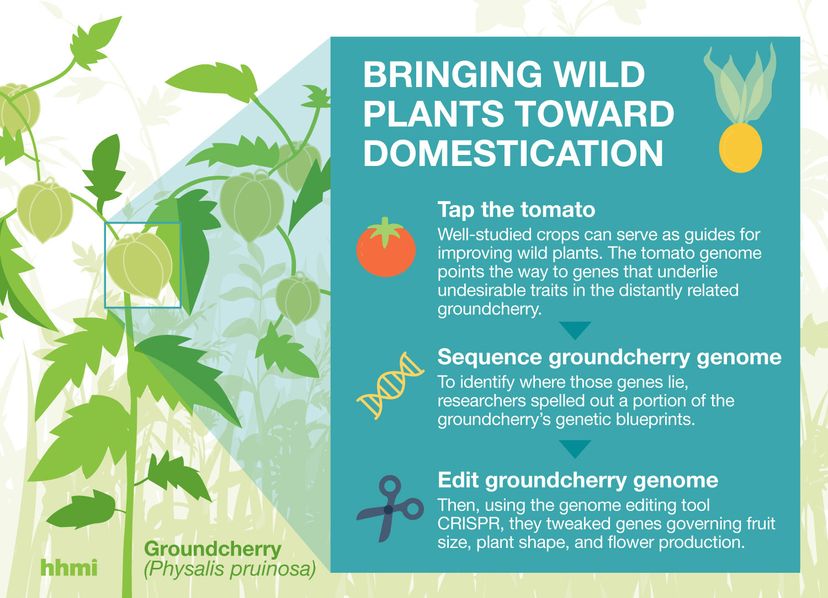

Plant scientists made headlines by using the gene-editing tool CRISPR to tweak some of the groundcherry's undesirable traits. By sequencing the plant's genome and comparing it to well-studied genomes like the tomato, researchers from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Boyce Thompson Institute were able to identify genes in the groundcherry that controlled for plant shape and fruit size. Using CRISPR, they edited the expression of those genes to produce more compact and bushy groundcherry plants with 25 percent heavier fruit. (Their findings were published in the journal Nature Plants on Oct. 1, 2018.)

Now, if they can figure out how to keep the ripe fruit from falling off the vine, the poor orphaned groundcherry might be "adopted" by large-scale commercial growers and show up in your local grocery store.

"It's a really exciting time to be in plant breeding right now," says Allen Van Deynze, a plant breeder and researcher with the University of California, Davis. "Plant breeding has always been defined as a science and art, and it's becoming a lot more science. That's because of the tools we're bringing to the table."

Van Deynze's interest in plant breeding technology goes way beyond rescuing a farmers market favorite. He is technical leader of the African Orphan Crops Consortium, an effort to sequence the genomes of 101 orphan crops in Africa like yams, finger millet, spiderplant and jujube. Even though millions of Africans rely on these crops, the most common varieties are often low in key vitamins and minerals. As a result, Van Deynze says that 37 percent of African children suffer the lifelong effects of malnutrition.

Advertisement