For ages, humans have divided our species into groups based upon skin color. The shade of one's complexion has been a powerful influence upon human culture, affecting everything from where we live and how much money we make to how much political power we have. And throughout history, racial divisions based upon skin color have led to violence and war.

That's all persisted because people cling to the belief that people of different skin colors are inherently different from one another, even though scientists have been telling us for years that race is a distinction that we invent in our minds, and that there isn't much actual difference in the genetic makeup of humans of various hues.

Advertisement

Now, an international team of researchers has published a groundbreaking study in the journal Science that may demolish the concept of race as a biological concept once and for all. Finding genetic variations for lighter skin color neither exist solely nor originate in European populations, challenging the idea of using skin color as a racial classification and showing that skin color may only be skin deep.

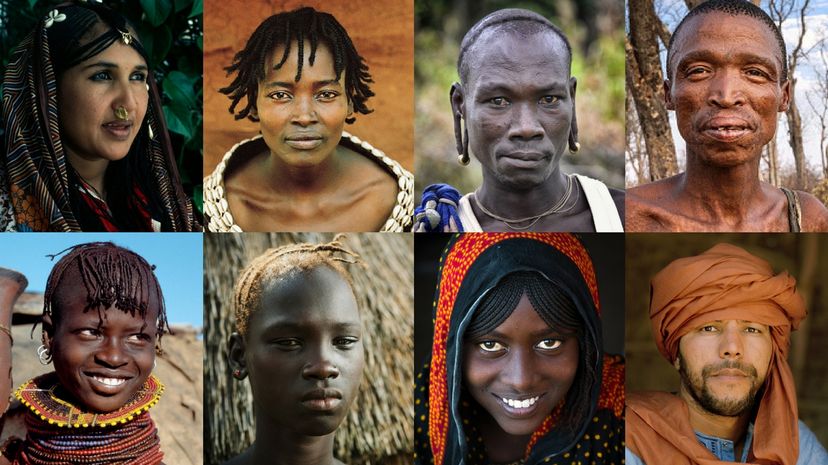

The scientists examined the genetic origins of skin color in Africans — who vary widely in shade from the dark skin of the Dinka people in South Sudan to the light-complexions of the San of South Africa. As an accompanying news story in the journal Science explains, the team used a light meter to measure the degree to which more than 2,000 individuals' skin reflected light. They also gathered blood samples for genetic studies.

The focus upon Africans was significant because most studies of the genetic underpinnings of race have been based upon European subjects — a choice that's provided an incomplete and perhaps misleading picture.

"This is part of a general bias that exists in human genetic studies which focus primarily on European populations," corresponding author Sarah Tishkoff, a genetics and biology professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says via email. "This results in a bias in our knowledge about genetic factors influencing both normal variable traits, like skin color, as well as disease risk. Specifically, studies that focused only on Europeans missed many of the genetic variants which we identified as associated with skin color. This is because there is less genetic and phenotypic (i.e. skin color) variation in that population compared to Africans. Also, many of the variants identified in Europeans are of recent origin."

"Prior to our study," says Tishkoff, "it wasn't recognized that variants associated with both light and dark skin are common in Africa and many are very old. Also, our study shows that both light and dark skin has been evolving in humans (prior to our study the emphasis has been on why light skin is adaptive in Europeans). Our study changes our understanding of the evolutionary history of variation in skin color."

The scientists identified eight genetic variations in four regions of the human genome that influenced skin shade. Using genetic information from nearly 1,600 people, they examined more than 4 million single nucleotide polymorphisms — places where the familiar DNA code made up of proteins represented by the letters G, A, T and C may differ by one "letter." Those genes turn out to be ones that have spread all over the planet — showing that many of the gene variations that cause light skin color in Europeans actually originated in Africa. (To be specific, the regions with the strongest associations were in and around the genes SLC24A5 and MFSD12.)

The ubiquitous nature of the skin-color genes, and their persistence over thousands of years, makes racial divisions seem pretty much meaningless from a biological viewpoint. Tishkoff told the New York Times that the study "dispels a biological concept of race." In her email to HowStuffWorks, she elaborates upon the larger potential impacts.

"I think that work strengthens what so many geneticists and sociologists already know — that race cannot be defined based on genetic criteria," she says. "There have been many abuses committed in the past, and in the present, based on that assumption so hopefully this and other studies will help dispel the notion of genetically defined racial groups."

Due to genetic variants shared among populations around the world, the new data also shines a light on human evolution, supporting the notion of a "proposed early migration event of modern humans out of Africa along the southern coast of Asia and into Australo-Melanesia and a secondary migration event into other regions."

Tishkoff hopes to build upon the study and explore other questions that remain about the genetics of skin color.

"We want to better understand how the biological mechanisms by which these variants are impacting skin pigmentation," she says. "Our study has implications for better understanding skin pigmentation disorders and melanoma risk. We are also looking at the genetic basis of other adaptive traits, as well as genetic and environmental factors influencing disease risk in ethnically diverse African populations."

Advertisement