There is great debate over what constitutes happiness. Is it the absence of pain or the presence of pleasure? Is it living a meaningful life? Or is happiness simply a neurological response to external stimuli, merely a flood of neurotransmitters expelled by specialized cells into the brain that produces the sensation of happy feelings and a sense of wellbeing?

If happiness is truly an electrochemical sensation -- and that increasingly appears to be the case -- then we should be able to manipulate it. One day, for instance, we could have access to a pill that induces the same response as does pleasant stimuli like being in love or the series of events that make up a good day.

Advertisement

A significant portion of the population may not take this "happy pill," if there ever is one. A 2006 survey in Great Britain found that 72 percent were opposed to taking a theoretically legal drug that induces happiness and had no side effects [source: Easton]. But how would we know what constitutes this "happy pill"? Will it be marketed that way?

It's possible the "happy pill" that the 2006 survey envisioned is already among us and its legal status has already come and gone. Most people call this drug MDMA or Ecstasy.

First invented in 1914 by a researcher at the pharmaceutical company Merck, MDMA was designed for use as a catalyst for use in producing other chemicals. Less than 70 years later, it was used as a psychotherapeutic catalyst instead; a drug that is capable of triggering the powerful emotions that are useful in psychological healing.

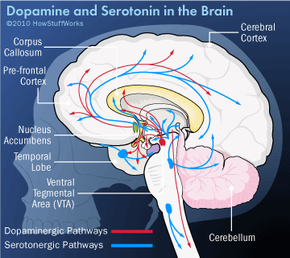

The drug signals the brain to expel serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters that are responsible for a stable mood and a sense of wellbeing. Therapists found that the flood of reassuring chemicals triggered by the drug was capable of generating feelings of empathy, giddiness and talkativeness in the people they prescribed it to and that it was particularly helpful in aiding victims of trauma to confront repressed memories. The drug served as something like an emotional lubricant.

Investigation into MDMA has been both extensive and hesitant. It was vetted for potential use as a brainwashing agent by the CIA in the 1950s. In the mid-1970s, a Dow Chemical employee rediscovered the drug and became the first to write a published report describing its euphoric effects. In the early 1980s, it was in use in its therapeutic capacity by psychiatrists. By 1985, the drug was outlawed in the United States.

Both pieces of legislation were based largely on the work of a single researcher who published evidence that MDMA causes irreversible damage to the brain. The second of these two groundbreaking studies was retracted in full by the researcher after it was discovered that he'd injected the stimulant methamphetamine, not MDMA, into the monkeys used in the experiment [source: Bailey]. With a renewed view that the drug is not as harmful as previously believed, the psychiatric community is once again looking to MDMA for its therapeutic use, as a tool in addressing post-traumatic stress disorder.

While MDMA isn't precisely the perfect "happy pill" envisioned in the 2006 survey -- it's illegal and its aftereffects include depressed moods in the user as the brain rebuilds its stores of neurotransmitters -- it's close enough for many people. Viewing MDMA as the closest thing we may ever get to a true "happy pill" reveals much about how we view happiness. The drug is outlawed and its users are regarded as fringe dwellers. It seems that most of us think happiness isn't an emotion to be synthesized.

Advertisement