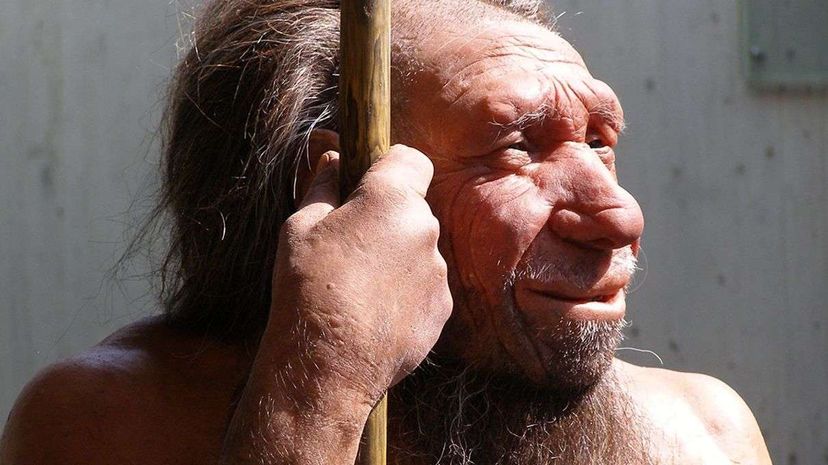

A lot of us have a little Neanderthal DNA in us. Modern humans of European or Asian descent inherited somewhere between 1 and 4 percent of our genes from this hominid that went extinct 30,000 years ago. We coexisted, and apparently more than coexisted, with them for as many as 5,400 years, but then they died out, and we remained. We were two very similar hominid species, and it's tough to pinpoint the advantage Homo sapiens of the time had over the Neanderthals: We both seemed to thrive and grow our populations during the last ice age, for instance. And Neanderthals actually had larger brains than modern humans, and seem to have done very "human" things, like bury their dead, cook, and make tools and personal ornaments. So what was the difference between a Neanderthal and a modern human of the time? And did our brain give us some sort of hidden advantage?

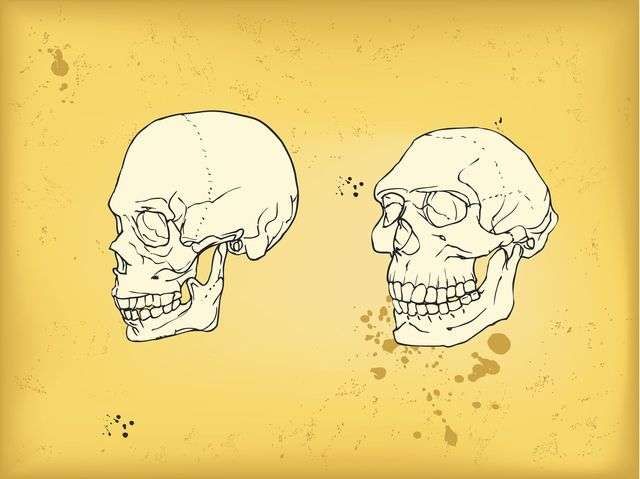

First of all, although your average Neanderthal had a larger brain than that of the last human you spoke to, it was probably comparable in size to the brain of the Homo sapiens of the time.

Advertisement

"Our ancestors had larger bodies than us, and needed larger brains to control and maintain those bodies," says Dr. Eiluned Pearce, a researcher in the Department of Experimental Psychology at Oxford, and coauthor of a 2013 paper on Neanderthal brains published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. "And Neanderthals were even larger-bodied than the modern humans living at the same time, so it's likely they would have needed a lot more neural tissue to control their bigger muscles."

Secondly, it's not just brain size that matters here, but brain organization. Neanderthals had very large eyes, which allows us to infer some things about their brains:

"There is a simple relationship between the size of the eyeball and the size of the visual area in the brains of monkeys and apes — and in humans, of course," says Pearce's co-author Dr. Robin Dunbar, professor of Evolutionary Psychology at Oxford. "From correlations known in monkeys, we can work out how much of the Neanderthal brain was dedicated to visual processing."

And it makes sense that Neanderthals would need an extra visual boost; they evolved at higher latitudes, where there's little sunlight during the long, dark winters. Pearce and Dunbar suggest that living in low-light conditions made it necessary for the Neanderthal brain to be dominated by a tricked-out visual processing system in the back. This allowed them to see in low-light conditions — but it also took up a lot of skull real estate.

Modern humans, on the other hand, put more energy into growing the front part of their brains, where all the complex social cognitive processes happen. This allowed them to grow their social networks to a size a Neanderthal might have found difficult to manage. So when caveman problems reared their ugly heads — cold, famine, disease — modern humans might not have been able to see quite as well as their Neanderthal counterparts, but they could maintain relationships with a larger group of people who could help them in times of trouble.

So, it's possible Neanderthals died out simply because they didn't have the people skills to get help from their buds when they needed it, which might have gradually decreased their numbers.

"It would have been an issue of social processing and social cognition for handling the complexities of human social relationships," says Dunbar. "Neanderthals would have been at the lower end of the distribution we find in normal human populations."

What might it have been like, then, to interact with a Neanderthal?

"We might find them a little on the slow, unsophisticated side," he says. "Probably pretty similar to many people we meet in everyday life, actually."

Advertisement