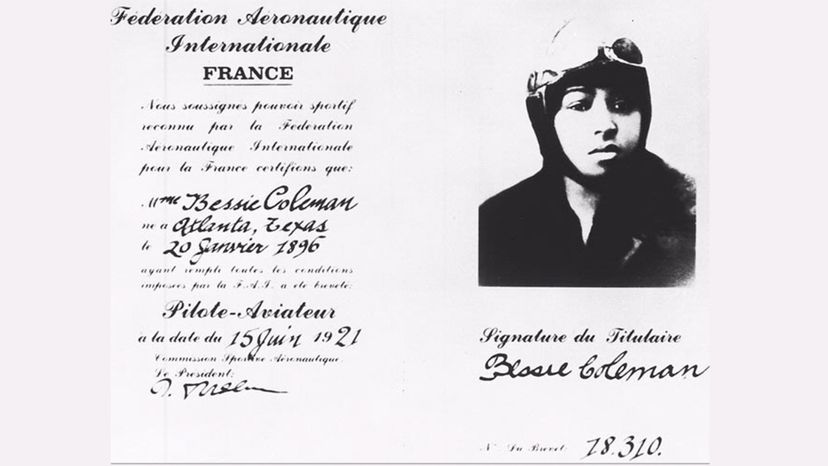

When we think of the early pioneers in the field of American flight, we'll hear about Amelia Earhart's solo trek across the Atlantic Ocean or Charles Lindbergh's nonstop journey in the Spirit of St. Louis, but the textbooks have often overlooked one pivotal figure who made an early mark on aviation history: Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman to become a licensed pilot, which she accomplished in 1921.

Coleman was born Jan. 26, 1892, and grew up in Waxahachie, Texas, the daughter of a mixed-race Native American and Black father and an African American mother, who both worked as sharecroppers. As the 12th of 13 children, Coleman was put to work in the cotton fields after her father left the family to return to his Native reservation. She attended primary school in a one-room wooden shack.

Advertisement

"But she was a good student — an avid reader. She read about a woman named Harriet Quimby — a woman pilot. She thought that might be something she would be interested in doing," says Dr. Philip S. Hart.

Hart has written two books on Bessie Coleman "Just the Facts: Bessie Coleman" and "Up in the Air: The Story of Bessie Coleman" and also served as an adviser to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum's "Black Wings" exhibit. The exhibit honors Black men and women who have advanced the field of aerospace, including not only aviators like Bessie Coleman, but also the Black Tuskegee Airmen who served in World War II.

Hart's own family history is inseparable from the history of Black aviation; Hart's mother's uncle, James Herman Banning, was the first Black American pilot to be licensed by the U.S. government in 1926. Banning and his co-pilot, Thomas C. Allen, became the first Black pilots to fly across America in 1932, according to Hart. Banning also became the first chief pilot of the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, which William J. Powell established in 1929 in honor of Coleman to support Black men and women in the field of aeronautics.

Coleman was preceded by Black male aviators, such as Charles Wesley Peters, the first African American pilot in the U.S., and Eugene J. Bullard, who flew for the French forces in World War I. But Coleman was the first African American female aviatrix to receive a pilot's license.

As a young woman, Coleman sought a different life for herself than the one her parents had, and she attended Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University (Langston University), but ended up dropping out for financial reasons.

She eventually made her way to Chicago, where her brothers lived, and she worked as a manicurist in a local salon. Her brother, who had returned from fighting during World War I, regaled her with stories of female pilots in France, joking that Coleman would never be able to fly like them. Such teasing only spurred on Coleman's ambitions to become a pilot.

While working in the salon, Coleman also met Robert Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Defender, which was a leading newspaper serving the Black community. Abbot would become her mentor, supporting her interests in aviation, and he would later write about her flight shows in his publication.

"One of the reasons he wanted to support her was because he knew her exploits would make for good stories in his newspaper," says Hart.

Advertisement