Each year, more than 3 million cats and dogs are euthanized at U.S. animal shelters [source: HSUS]. That's about half of all cats and dogs that enter shelters. And you can bet someone's beloved Fluffy or Fido is among those that suffer the avoidable fate of euthanasia. What if there were a way to prevent these tragic deaths? Imagine the glee of a grieving pet owner when the shelter calls to say it's found little lost Fido. Microchip technology makes more of these emotional reunions possible.

Advertisement

In Hurricane Katrina's aftermath, thousands of pets were left stranded and woefully separated from owners. The problem highlighted the need for a permanent identification system to reunite animal with master. Microchip implants offer one solution. In addition to tags, microchips theoretically provide a surefire, permanent identification method for pets. Dognappers can easily remove dog tags, but it would take a difficult surgical procedure to remove a microchip.

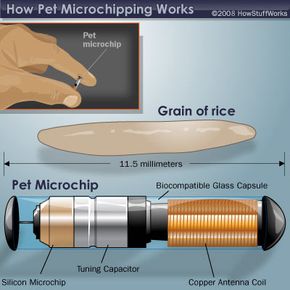

A microchip is no bigger than a grain of rice, and veterinarians can implant the chips into all kinds of pets -- from reptiles and birds to cats and dogs. The device carries a number, and this number is plugged into a database that includes the name and contact information of a pet's owner. AVID and HomeAgain are the largest sellers of the microchips. AVID claims that its microchips help reunite as many as 1,400 pets with their owners every day, and HomeAgain touts a growing total of more than 400,000 pet recoveries [source: AVID, HomeAgain].

In Europe, pet microchips are becoming more standard -- about a quarter of European pets have a microchip implant. But the idea isn't quite as popular in the U.S., where only about 5 percent of the approximately 130 million dogs and cats are microchipped [source: Springen, USDA]. Some communities, such as El Paso, Texas, have shown more interest in the microchips. That city has begun requiring owners to microchip dogs, cats and ferrets [source: City of El Paso, Texas].

But not everyone thinks the pet microchip is a good thing. In this article you'll learn about the benefits of these chips and the controversy that surrounds them. Are they bad for a pet's health? Is the competition among pet microchip companies hurting the devices' effectiveness? First, let's learn how these tiny devices work.