In an ad that aired on TV in New York, a man named Burton Aldrich stares at the camera and tells the viewer, "I am in extreme pain right now. Everywhere. My arms, my legs, are feeling like I'm dipped in an acid." Aldrich is a quadriplegic confined to a wheelchair, and the best treatment for his overwhelming pain, he says, is marijuana. He continues, "Within five minutes of smoking marijuana, the spasms have gone away and the neuropathic pain has just about disappeared."

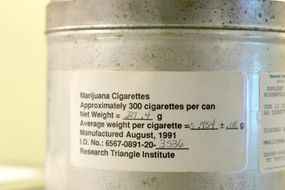

To some, medical marijuana is a contradiction in terms, immoral or simply illegal. But to Aldrich and numerous people in the United States and around the world, marijuana, or cannabis, represents an essential medicine that alleviates debilitating symptoms. Without it, these people wouldn't be able to treat their conditions. Aldrich thinks he would be dead without marijuana. Others, like Dr. Kevin Smith, who was also featured in these pro-medical marijuana ads, can't treat their conditions for fear of breaking the law. Smith says that, save for a trip to Amsterdam where he tried marijuana, the autoimmune disorders he suffers from have prevented him from sleeping soundly through the night for the last 20 years.

Advertisement

In states in which it's legal, doctors recommend medical marijuana for many conditions and diseases, frequently those that are chronic. Among them are nausea (especially as a result of chemotherapy), loss of appetite, chronic pain, anxiety, arthritis, cancer, AIDS, glaucoma, multiple sclerosis, insomnia, ADHD, epilepsy, inflammation, migraines and Crohn's disease. The drug is also used to ease pain and improve quality of life for people who are terminally ill.

So how, exactly, does medical marijuana work to treat these conditions? Why, if this medicine is so effective for some people, does it remain controversial and, in many places, illegal? In this article, we'll take a look at the medical, legal, and practical issues surrounding medical marijuana in the United States. We'll examine why some people, like Burton Aldrich, depend on it to live normally. We'll also examine some of the intriguing intersections between pharmaceutical companies, the government and the medical marijuana industry.

Advertisement