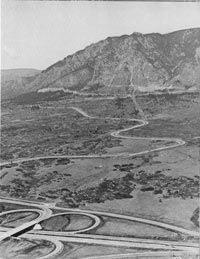

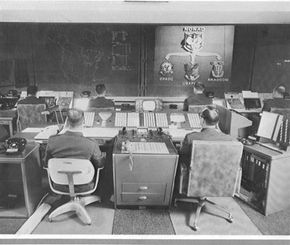

NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, is a military operation run jointly by the United States and Canada. Originally headquartered in a massive complex built within a hollowed-out mountain near Colorado Springs, NORAD's goal is to monitor all possible approaches to the United States via air and space for potential attacks. Created at the height of Cold War paranoia, NORAD is a technological wonder that has been forced to adapt continually to new threats.

In this article, we'll take a brief look at the history of NORAD, the technology behind its operations and where the command stands today.

Advertisement

Deter, Detect, Defend

To understand NORAD, it's important to understand the Cold War fears that spawned it. Consider this quote, written in 1967:

NORAD's motto is "Deter, Detect, Defend." Deterrence was accomplished simply through the fact of NORAD's existence. "Potential enemies know that they would suffer disastrous consequences at once if they should be so foolish as to launch an attack against the United States or Canada. Full knowledge of these facts is considered the greatest safeguard and deterrent against sneak attack," reads the introduction of a NORAD guidebook published in 1970 [source: Hough]. In many ways, the creation of NORAD was an act of Cold War propaganda. This is not to suggest that NORAD wasn't capable of doing the things the United States claimed it could do, just that the claims were at least as important as the technology itself.

Detection was accomplished with an ever-growing series of radar installations stretching across Canada. If you look at a globe from directly above, you can see that the shortest path between the United States and Russia is through the Arctic, placing Canada directly between the two Cold-Warring nations. NORAD's "radar fence" was meant to act as a first line of defense, giving as much advance warning as possible when attack planes or missiles were launched toward the United States or Canada. This would provide time to react (with retaliatory missiles) and possibly affect some form of evacuation or allow civilians to reach bomb shelters.

Special squadrons of Air Force fighters and bombers (Strategic Air Command, or SAC squadrons) were set up to perform the defense aspect of NORAD's motto. Able to scramble and take to the air on a moment's notice, these planes could be used to intercept and destroy incoming enemy aircraft. Incoming missiles couldn't be dealt with in any practical way, so bombers would be sent to fire missiles at Russia, ensuring the mutual destruction of both nations.

Advertisement