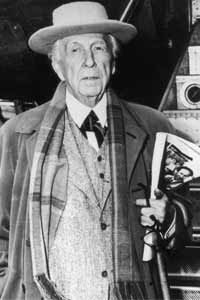

Lively and mutable, always game to coax potential clients or scold them when they wouldn't adhere to his exacting vision, Frank Lloyd Wright was an ambitious visionary, a groundbreaking pioneer who helped mold American architecture in the 20th century and is hailed by many as the greatest architect produced by America to this day. He designed more than 1,000 buildings over a 70-year time span, about 500 of which were built.

But Wright was more than just a captain of architecture, more than just a name on some historical markers outside aging, if lovely, homes; Wright was a man. He had love affairs and hobbies, he had bad habits and cherished qualities.

Advertisement

For instance, Wright had a great love of Japanese prints. The serene and aesthetic artwork influenced his practice of infusing architecture with the natural beauty of its surroundings, and he would often fully merge the two through his precise choice of location and design elements. His large collection of artwork from the East included gold screens, Chinese paintings, antique rugs and embroideries, woodcuts, pottery, bronzes and sculptures.

Wright also was a fan of fast cars; he was one of the first to own a car in his Oak Park neighborhood near Chicago, where he lived and worked for many years. His four-cylinder customized Stoddard Dayton would roar through the city streets, earning him plenty of speeding tickets.

It was on his fashionable lifestyle and expensive hobbies like these that Wright was forever squandering his money and negotiating with various debtors and patrons. He postponed the payment of bills and paychecks, refinanced mortgages, cajoled extra funds out of clients, friends and benefactors, and his projects notoriously always seemed to run over budget.

But he always seemed to regain success with his designs. Wright's architecture was above all organic, attuned to the nature around it, whether that setting be tranquil or willful. To look at one of his buildings from the street corner is to be impressed by its beauty and shape, but walk inside and you see where he was the true master -- he ruled interior spaces, down to the last chair and stained glass accent.

Wright was also so particular about the furniture and decorations that accompanied a home he designed, that it often went poorly when he returned to visit, only to find things not to his taste. On at least one occasion, Wright set the decor back the way he liked it, much to the dismay of the lady of the house.

On the next page, we'll discuss some of the basic facts of Wright's life. You'll notice, though, that it's titled the Women of Frank Lloyd Wright -- that's not an accident. Continue to the next page to find out why.

Advertisement