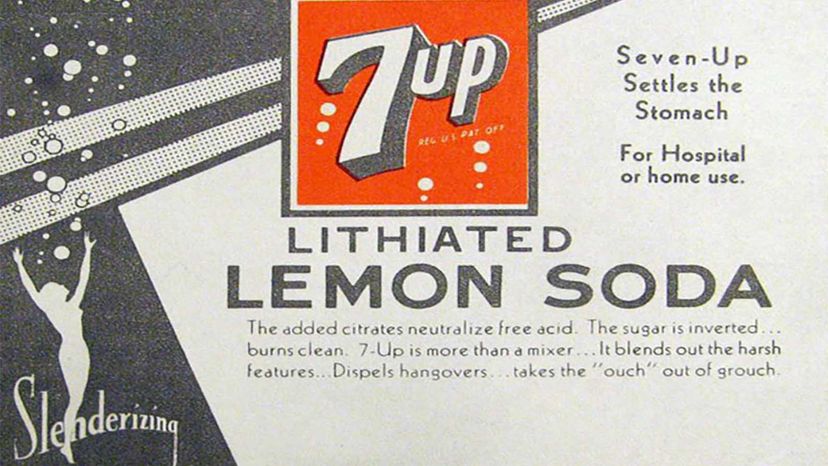

In 1929, 7UP soda was advertised as a "Bib-label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda" and later 7UP Lithiated Lemon Soda. The popular drink did actually contain lithium citrate, a compound made from the element lithium, the same one found in today's lithium-ion batteries. There is no confirmed explanation for the 7 in 7UP, but some people have speculated it's because lithium's atomic mass is close to 7 (it's 6.94, but perhaps they rounded up).

Still, lithium citrate (lithium salt) was an ingredient in the beverage between 1929 and 1948 when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned it from use in soda and beer.

Advertisement

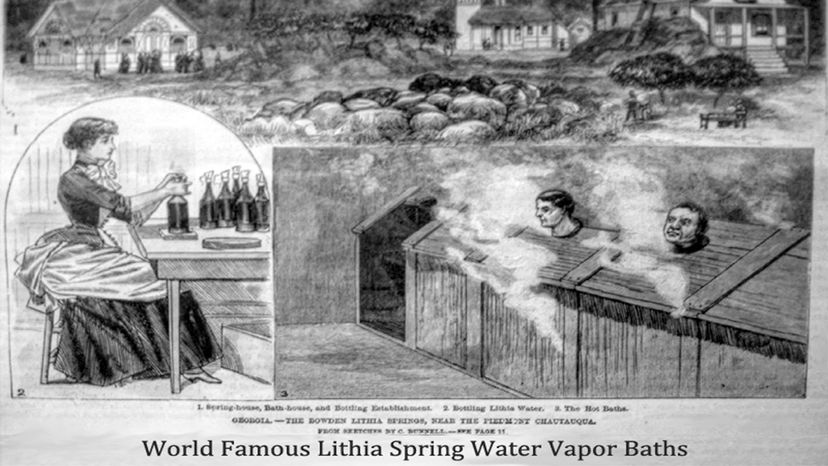

Why were companies putting lithium in their beverages in the first place? For centuries, lithium hot springs were thought to be medicinal, and throughout the 1800s, lithium was used to treat gout — including "brain gout." It was also being prescribed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for mania and melancholic depression, so the element had a good reputation.

But today lithium is in higher demand than ever before. And while most people probably think of the element in terms of batteries for laptops and EVs, the element is used for things well beyond technology. In fact lithium is still used to treat some mood disorders; it's been used in high-tech lenses at the FERMILAB proton conversion system for decades; and it helps stabilize glassware and ceramics. There are even some who believe microdosing it would be beneficial for mental health (more on that later).

Advertisement