And then there's the fact that the ocean is rarely clear, but is instead teeming with tiny plant and animal life or filled with suspended sediment or contaminants. Oceanographers monitor the ocean's color as doctors read the vital signs of their patients. Color seen on the ocean's surface reflects what's going on in its vast depths.

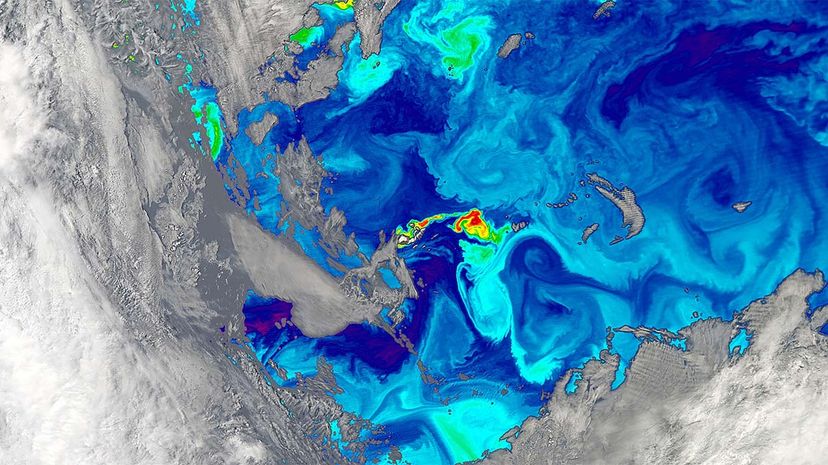

Feldman, who's based at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, studies images taken by the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWiFS) satellite, launched in 1997. From its perch, more than 400 miles (644 kilometers) above Earth, the satellite captures Van Gogh-like swirls of the ocean's colors. The patterns are not only mesmerizing, but they also reflect where sediment and runoff may make water appear a muddy brown color and where microscopic plants, called phytoplankton, collect in nutrient-rich waters, often tinting it light green.

Phytoplankton use chlorophyll, which is a green pigment, to capture energy from the sun to convert water and carbon dioxide into the organic compounds. Through this process, called photosynthesis, phytoplankton generate about half of the oxygen we breathe. While most phytoplankton give ocean water a green tint, some lend it a yellow, reddish or brown tint, Feldman says.

Oceans with high concentrations of phytoplankton can appear blue-green to green, depending on the density. Greenish water may not sound appealing, but as Feldman says, "If it weren't for phytoplankton we wouldn't be here." Phytoplankton serve as the base of the food web and primary source of food for zooplankton, which are tiny animals eaten by fish. The fish are then eaten by bigger animals like whales and sharks.

It's when oceans become polluted with runoff that the amount of phytoplankton can escalate to unhealthy levels. Phytoplankton feed on the pollutants, flourish and die, sinking to the bottom to decompose in a process that depletes oxygen from the water.