In 1849, famed Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky found himself facing death by firing squad for his political activities. But death never came; it was a staged execution, and Dostoyevsky instead found himself headed to a labor camp in Siberia.

His mock execution seems to have affected him for the rest of his life, however. Many of his later novels focused on criminals, violence and forgiveness, all subjects very familiar to the author. Needless to say, Dostoyevsky's experience wasn't unique.

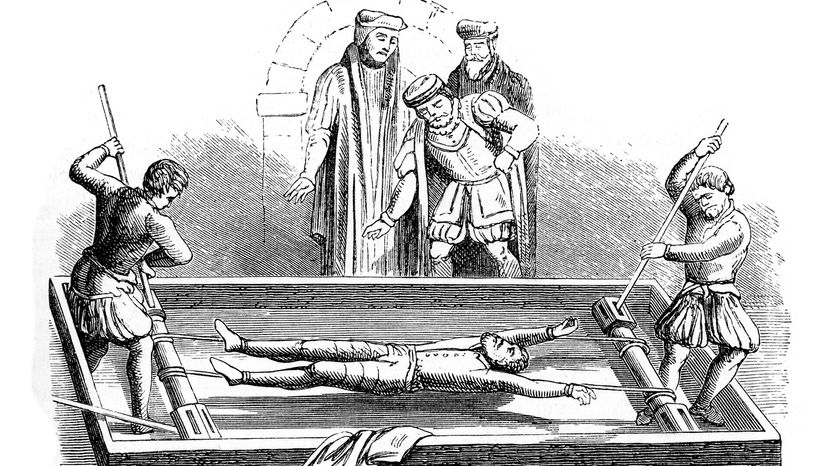

Mock execution methods are any situation in which a victim feels that his or her death — or the death of another person — is imminent or has taken place. It could be as hands-off as verbally threatening a detainee's life or as dramatic as blindfolding a victim, holding an unloaded gun to the back of his or her head and pulling the trigger.

Any clear threat of impending death falls into the category of mock executions. Waterboarding, the method of simulated drowning, is also an example of mock execution.

The U.S. Army Field Manual expressly prohibits soldiers from staging mock executions [source: Levin]. But reports of some U.S. military members staging these executions have emerged from the Iraq War.

For example, in 2005, one Iraqi man questioned for stealing metal from an armory was tortured by being asked to choose one of his sons to die for his crime. When his son was taken around a building, out of the man's sight, he was led to believe that they executed his son when he heard gunshots fired.

Two years earlier, two Army personnel were under investigation for staging mock executions. In one circumstance, an Iraqi was taken to a remote area and made to dig his own grave, and soldiers pretended he would be shot [source: AP].

The U.S. military is not the only group to violate international law regarding mock executions as torture. In 2007, Iran's Revolutionary Guard captured 15 Britons. After their second night, the prisoners lined up facing a wall, blindfolded and bound. Behind them, the detainees heard guns cocked, followed by the clicks of firing hammers falling against nothing [source: Kelly].

Despite bans against them, mock executions continue as a means of torture — perhaps because of their effectiveness in breaking a detainee's will. The effects of such threats on the victim's life are deep and lasting: The Center for Victims of Torture reports that torture victims who've undergone mock executions described flashbacks in which they felt as though they had already died [source: CVT].