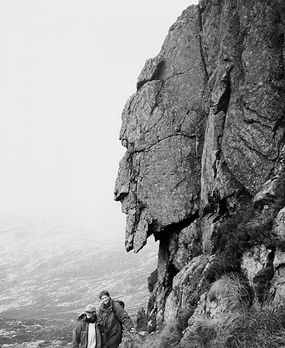

A common term most first-year psychology students learn is "apophenia" — the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns in random things, like objects or ideas. There are plenty of ways we see apophenia play out in the real world. Take mimetoliths.

"A mimetolith is a natural rock feature that resembles a living form in nature — usually a face a human head, or animal," geologist Sharon Hill, owner of SpookyGeology.com writes via email. "The word was coined by Thomas Orzo MacAdoo but first appeared in print from R. V. Dietrich in 1989. The term is derived from the Greek words mimetes (an imitator) and lithos (stone)."

Advertisement

According to Hill, mimetoliths have sort of a Magic Eye quality about them — you know them when you see them, but not everyone sees them right away. "It is striking and invokes powerful feelings," she says. "Humans readily recognize patterns, particularly faces and human forms, in the sky and landscape. Our brains are programmed to do this. So there are many notable features around the world that appear to resemble faces or heads. We tend to ascribe significant meaning to what is just a natural formation and bestow special values to these features no matter if they are tiny or huge."

Hill says mimetoliths are often linked to everything from cultural traditions to conspiracy theories. "Familiar figures emerging from solid rock must have been a powerful symbol to early people that supernatural agencies had a hand in the formation of the Earth," she says. "Most of these features are associated with folklore about the creation of the land or an ancient time when the world was enchanted. It makes us feel that it is enchanted, still."

One fascinating fact to keep in mind about mimetoliths is that in many ways, they're fleeting. "The most famous mimetoliths in the world at any time are truly temporary and ever-changing," Hill says. "Gravity, ice, water and wind will eat away at rock."

So, to celebrate these ephemeral natural wonders, take a look at these four famous mimetoliths and see if you can find the features many have said make them special.

Advertisement