Egyptian Mummification

In the course of its 3,000-year run, Egyptian embalming (artificial mummification) passed through many stages. As we learned in the last section, the practice began with the natural preservation qualities of the arid desert ground. For many generations, the Egyptians buried their dead this way -- in the hot sand, with a few belongings but no casket or housing. As their concept of the afterlife evolved, the Egyptians became concerned about the comfort of their departed family members. They began covering the bodies with long wicker baskets and later with sturdy wooden boxes. Eventually, this led to fully enclosed coffins and tomblike housings.

Of course, with the body fully enclosed, it was not exposed to the drying properties of the sand. The fluids remained in the body; the bacteria thrived, and the flesh naturally decomposed. This left the Egyptians with a real quandary -- they didn't want to leave their loved ones completely covered in sand, but they also didn't want the bodies reduced to skeletons. To ensure survival and comfort in the afterlife, the Egyptian scientists had to figure out a way to replicate the preservative qualities of the desert.

Advertisement

In the early days of mummification, the embalmers concentrated mostly on keeping the body away from the elements. They wrapped it up tightly in strips of linen soaked with resin. With careful application of these bandages, the embalmers were able to create shapely forms, giving bodies the filled-out appearance of the living. These wrapped corpses were impressive to be sure, but in most cases the bandages did little to stop decomposition. Bacteria survived inside, and the body was eventually reduced to a skeleton.

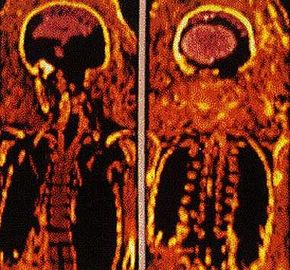

Through experimentation, the Egyptians discovered that decomposition worked largely from the inside out. Bacteria collected first in the body's internal organs and moved on from there. To stop the putrefaction process, the embalmers realized, they would have to remove the internal organs. This, combined with the discovery of the natural drying agent natron, led to the famous Egyptian mummies we know today.

The science and theology of embalming continued to evolve over the years, so there is no single Egyptian ritual. But the standard practices of the New Kingdom's 18th through 20th dynasties (1570 to 1075 B.C.), an era that produced some of the best preserved mummies, are fairly representative.

Egyptologists have determined that the mummification rituals were performed in the Red Land, a desert region removed from heavily populated areas, with easy access to the Nile River. Reason suggests that the embalmers may have worked in open tents, rather than solid structures, in order to allow proper ventilation.

Before beginning the embalming process, the Egyptians took the body to the Ibu, the "Place of Purification." In this house, they washed the body in water gathered from the Nile. This represented a sort of rebirth, as the person passed from one world into the next. Once the body was cleaned, the embalmers carried it to the Per-Nefer, the "House of Mummification," where they began the embalming process.