On the most basic level, human beings are made up of five major components:

- A body structure

- A muscle system to move the body structure

- A sensory system that receives information about the body and the surrounding environment

- A power source to activate the muscles and sensors

- A brain system that processes sensory information and tells the muscles what to do

Of course, we also have some intangible attributes, such as intelligence and morality, but on the sheer physical level, the list above about covers it.

Advertisement

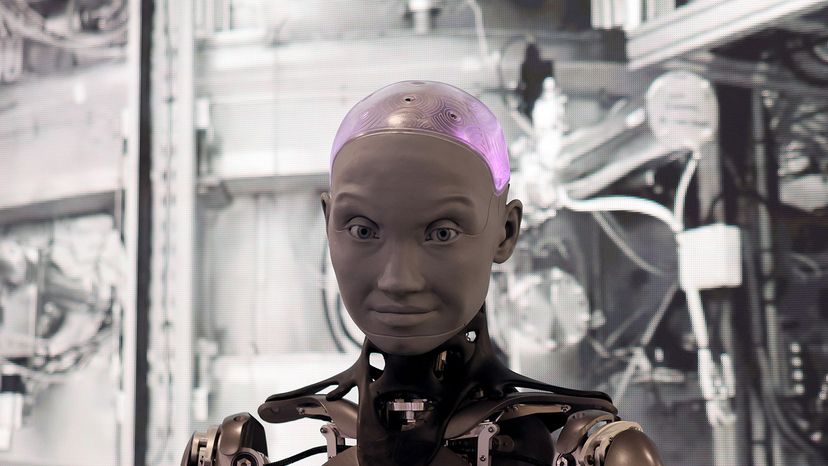

A robot is made up of the very same components. A basic typical robot has a movable physical structure, a motor of some sort, a sensor system, a power supply and a computer "brain" that controls all of these elements. Essentially, robots are human-made versions of animal life — they are machines that replicate human and animal behavior.

Joseph Engelberger, a pioneer in industrial robotics, once remarked, "I don't know how to define one, but I know one when I see one!" If you consider all the different machines people call robots, you can see that it's nearly impossible to come up with a comprehensive definition. Everybody has a different idea of what constitutes a robot.

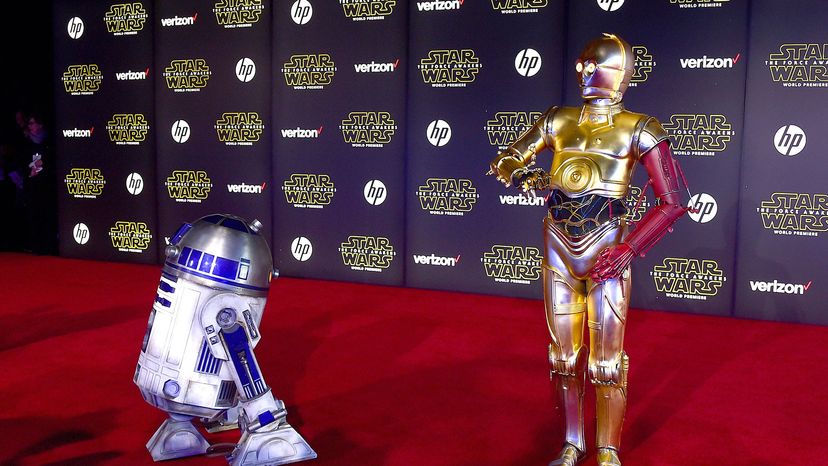

You've probably heard of several of these famous robots:

- R2-D2 and C-3PO: The intelligent, speaking robots with loads of personality in the "Star Wars" movies

- Sony's AIBO: A robotic dog that learns through human interaction

- Honda's ASIMO: A robot that can walk on two legs like a person

- Industrial robots: Automated machines that work on assembly lines

- Lieutenant Commander Data: The almost-human android from "Star Trek"

- BattleBots: The remote control fighters from the long-running TV show

- Bomb-defusing robots

- NASA's Mars rovers

- HAL: The ship's computer in Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey"

- Roomba: The vacuuming robot from iRobot

- The Robot in the television series "Lost in Space"

- MINDSTORMS: LEGO's popular robotics kit

All of these things are considered robots, at least by some people. But you could say that most people define a robot as anything that they recognize as a robot. Most roboticists (people who build robots) use a more precise definition. They specify that robots have a reprogrammable brain (a computer) that moves a body.

By this definition, robots are distinct from other movable machines such as tractor-trailer trucks because of their computer elements. Even considering sophisticated onboard electronics, the driver controls most elements directly by way of various mechanical devices. Robots are distinct from ordinary computers in their physical nature — normal computers don't have physical bodies attached to them.

In the next section, we'll look at the major elements found in most robots today.

Advertisement