The MQ-9 Reaper represents the cutting edge of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, but the idea of using unmanned entities to wage aerial war isn't new. In the early days of the United States' involvement in World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved research into a plan to release bomb-wielding bats from airplanes.

The bombs -- small kerosene-filled incendiary tubes that operated on a chemical time-release fuse -- were connected to a surgical clip with a short piece of string, and the clip was attached to a bat's chest. The idea was to cool the bats down into a state of forced hibernation, initiate the chemical fuse, attach the device, load the placid bats onto a plane and then release them over a target area. Ideally, the bats would seek shelter in buildings, chew through the string (separating themselves from the devices) and then the device would detonate, setting enemy infrastructure on fire.

Advertisement

What actually happened is that a bunch of hibernating, bomb-laden bats were dropped to their deaths from an airplane. Six thousand bomb-rigged bats gave their lives in these military experiments.

The experiments did give researchers insight into possible problems that UAVs may cause or encounter. For one, it was unlikely that many people would support the type of loose targeting standards enforced by bomb-laden bats that flew astray into civilian territory. During the course of the experiments, researchers witnessed this problem firsthand when some of the armed bats escaped and fire-bombed an Army airplane hangar and a general's car.

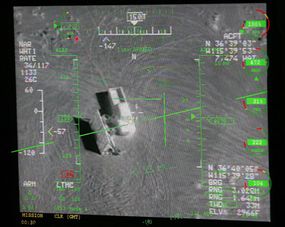

Fast-forward to the present, in which unmanned combat drones are flying over the skies of Iraq and bombing caves in Afghanistan Before long, these drones will be sent in formation not to search quietly and relay information about enemy troops or fortifications as previous generations of UAVs have, but to attack them. The MQ-9 Reaper is nothing short of an unmanned aerial bomber squadron -- and it'll only become more sophisticated and lethal.

In this article, we'll learn about the robotic combat systems in use and what systems the military is developing for the future. But first, we'll take a look at the history of unmanned flight.