Death Masks: An Artist's Most Patient Subject

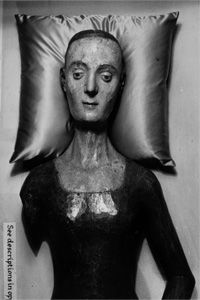

Before photography came along, death masks served as a reference for painters and sculptors to depict the noble and the famous. They were extremely, even eerily, accurate impressions of their subject, made from plaster or wax in the first hours after death [source: Gibson]. Armed with them, artists could paint and sculpt portraits for royal halls and even create three-dimensional representations for a tomb. If you've ever been to Europe and visited the tombs of ancient cathedrals, then you've seen the faces of nobles copied from death masks.

Ancient Egyptians and Romans also made death masks, though many were just likenesses of the deceased rather than plaster or wax impressions of the face. When Egyptians mummified a body, the face also had to be bandaged. The soul would need a mask to recognize its own body, as well as have a face for the afterlife. The masks became elaborate, covered in gold and jewels. King Tut's funerary mask is one of the most elaborate and famous examples. Less important or less wealthy people had to make do with masks made of linen or papyrus and painted gold.

Advertisement

The ancient Romans used their death masks as effigies, though their preferred medium was wax. Again, these masks weren't proper death masks, but Roman nobles, did, however, have imagines -- wax masks or busts of their high-ranking ancestors. A full wax cast was made of Julius Caesar's body after his death, stab wounds clearly visible. Mark Antony showed this effigy to a crowd, inciting a riot that burned down the senate building [source: History Channel].

The oldest-known European example of a death mask belongs to the face of Edward III, king of England. He reigned from 1327 until his death in 1377 [source: Gibson]. With the dawn of the Renaissance, artists began to perfect realistic portraits of their subjects. Death masks weren't necessarily needed anymore, so why keep making them?