On Sept. 14, 2011, NASA announced plans to construct and launch the most powerful rocket ever to match its might against Earth's gravity. In various forms, this blasting behemoth will constitute the driving force behind the American space program for the foreseeable future.

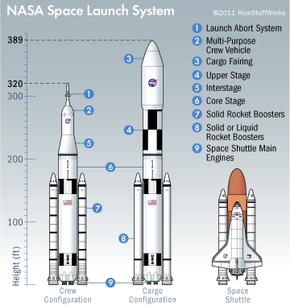

Rising from the ashes of the U.S. space shuttle program, which flew its final mission in July 2011, and its stillborn successor, the Constellation program, which was cancelled in February 2010, the Space Launch System (SLS) will inherit characteristics of both of its predecessors. Its technological lineage extends further down the family tree as well, to the former heavyweight champ, the Saturn V workhorse that launched Americans moonward more than 40 years ago.

Advertisement

The plan promises a launch vehicle made up of one part tried-and-true rocket know-how and one part state-of-the art technologies and materials. A dash of modularity will enable mission planners to tailor individual SLS builds to the demands of various missions, which NASA says will range from near-Earth milk runs to Mars exploration and beyond.

If you think that sounds like a lot to ask from a single system, you're not alone. The SLS has been mandated by Congress to serve so many masters in so many ways, it's a wonder it's not required to sing, dance and make great waffles to boot. This extraordinarily broad vision, combined with the underlying political dealing driving the system's design, has led critics to question whether the SLS can succeed at all.

In this article, we'll take a peek under the hood of this new heavy lifter. We'll also look at why some consider the SLS to be less of a phoenix and more of a turkey.

Advertisement