If the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union were an athletic competition, it would look more like a decathlon than a linear 5K. Allowing each country to flex its Cold War muscles, the space race of the 1960s symbolized the power struggle between the United States and the USSR during that tenuous time after World War II.

The first successful orbit of the Soviet's artificial satellite Sputnik I on Oct. 4, 1957, sent the United States into a galactic frenzy. Roughly the size of a watermelon, Sputnik was the starting pistol that launched the space race. In the struggle to catch up, U.S. President Eisenhower signed into creation the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1958. From here, NASA and its astronauts would take center stage in the peacetime pursuit to beat the Soviet Union and its cosmonauts.

Advertisement

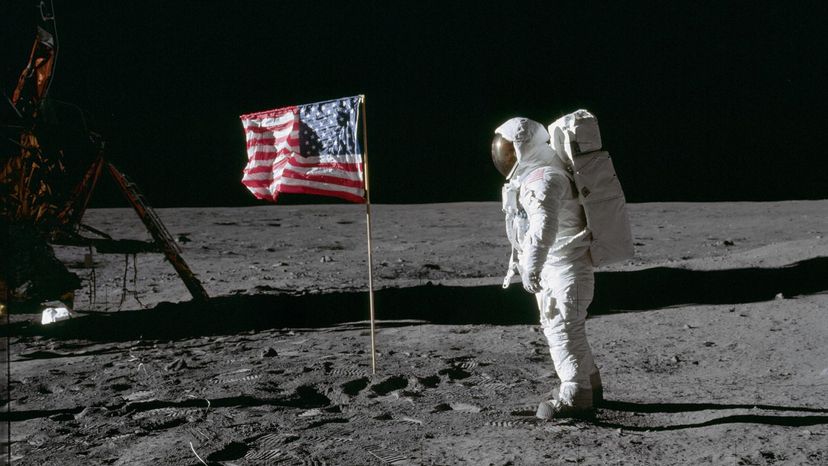

On May 25, 1961, President Kennedy announced what would become the space race's finish line: the moon. Following cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin's inaugural trip into space, Kennedy's vow to get a man on the moon by 1970 raised the bar in the space rivalry with something that would overshadow the USSR's previous string of successes. As though playing an international game of poker, Kennedy put all the American chips on the table.

President Kennedy's proclamation was a deft political move. In fact, both the United States and the Soviet Union spied on each other using satellite photography that was folded into their space agendas [source: National Air and Space Museum]. For instance, the U.S. satellite Corona took more than 800,000 photographs from 1960 to 1972 to learn just how much detail the images could capture [source: National Air and Space Museum].

With all this going on, who crossed the finish line first? Since the United States would put a man on the moon in 1969, did that effectively end the race? Read on to find out.