Key Takeaways

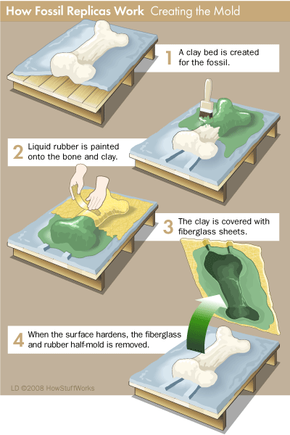

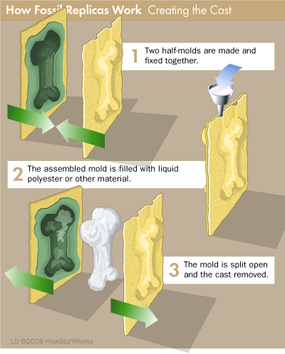

- Fossil replicas are made using a mold and cast method, where the original fossil is used to create a detailed mold, which is then filled with resin or plastic to form a cast.

- These replicas allow museums and researchers to display and study dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures without risking damage to the original fossils, which are often too heavy or fragile.

- Advanced techniques like rapid prototyping, using CT scans for 3-D mapping, and materials such as dental molding for fieldwork, make it possible to create accurate and detailed reproductions of fossils.

Argentinosaurus is one of the largest dinosaurs ever discovered. You can see what its skeleton looked like at Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Ga. The Argentinosaurus skeleton in the museum's great hall dwarfs everything else in the room. From nose to tail, it's more than 120 feet (36.5 meters) long, and some of its vertebrae are more than 5 feet (1.5 meters) wide. If you walk up the stairs to the second-floor landing to get a better look, the dinosaur's hip will be roughly at eye level.

But when you look at this prehistoric giant, you're not seeing prehistoric bones. The bones in the Argentinosaurus skeleton are fossil replicas made of hollow plastic. This doesn't mean a trip to Fernbank to see dinosaur skeletons would be a waste, though. Without fossil replicas, no one would be able to see an Argentinosaurus skeleton without going to Argentina.

Advertisement

This is just one reason why a museum or collector might have fossil replicas instead of real fossils. Researchers and museums can use replicas to share rare fossils or fill in missing gaps from skeletons. Real dinosaur fossils can also be too heavy to be mounted in a museum, making lightweight replicas a more practical choice.

Replicas can even help protect fossils. The process of making the replica gives curators and paleontologists a chance to evaluate the original, repair damage and take steps to preserve the fossil if necessary. Some real specimens are so fragile that displaying them in a museum would eventually cause their destruction. Museums put exact replicas on display while placing the originals in protective storage. Transporting replicas from one museum to another is usually safer than transporting originals -- there's less chance of losing or destroying the original specimens.

And while most paleontologists conduct research using real fossils, replicas can act as stand-ins, too. For example, because it's so big, studying the way an Argentinosaurus moved would be almost impossible using a full-sized skeleton. But by creating a small-scale replica, researchers could move bones around to figure out how they moved in relation to each other.

For fossil replicas to do all this, they have to be as accurate as possible. But how can a replica be finely detailed, lightweight and sturdy all at the same time? We'll look at the making of accurate reproductions next.

Advertisement