Key Takeaways

- The oldest known diseases include cholera, typhoid, leprosy, smallpox, rabies, malaria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, trachoma and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, each documented through various means including bone lesions, DNA testing and ancient texts.

- Diseases like cholera and typhoid thrived in dense populations and were spread through contaminated water sources, while leprosy's dormancy allowed it to spread unnoticed for years.

- Genetic evidence linking mitochondria to ancient bacteria suggests that some of the oldest diseases have fundamentally influenced human evolution and the development of life as we know it.

In the study of ancient diseases, nothing speaks like the dead.

"Bone abnormalities are a strong identification source," said Dr. Anne Grauer, anthropologist at Loyola University Chicago and president of the Paleopathology Association, during a personal interview. So it's relatively easy to date tuberculosis due to the lesions it leaves on bones. Pneumonia may be more ancient than TB, but lung tissue doesn't hold up so well after being buried.

Advertisement

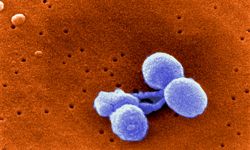

"Another source for dating diseases is genomic data," said Dr. Charlotte Roberts, archaeologist at the University of Durham and author of the book "The Archaeology of Disease." DNA testing of samples from mummies and skeletons can conclusively identify disease. And even without the evidence of a body, genes in existing samples of TB and leprosy bacteria suggest prehistoric origin.

But the most difficult trick in defining the oldest known diseases may be in how you define the word "disease." For the purposes of this article, we'll explore only human, infectious, viral or bacterial diseases. So nix tooth decay, psoriasis, gout, obesity, rickets, epilepsy, arthritis and other human difficulties that are perhaps best classified as "conditions."

Notably absent from this list are some of history's biggest killers, including influenza, measles and the black plague. This is because these diseases require a level of population density that didn't develop until humans began living in cities. Influenza, measles and the plagueare social. Malaria isn't.

We've listed 10 of the oldest known diseases, listed in no particular order. On the next page, we'll get started with a condition that thrives in close quarters.