It's dark out, and you're home alone. The house is quiet other than the sound of the show you're watching on TV. You see it and hear it at the same time: The front door is suddenly thrown against the door frame.

Your breathing speeds up. Your heart races. Your muscles tighten.

Advertisement

A split second later, you know it's the wind. No one is trying to get into your home.

For a split second, you were so afraid that you reacted as if your life were in danger, your body initiating the fight-or-flight response that is critical to any animal's survival. But really, there was no danger at all. What happened to cause such an intense reaction? What exactly is fear? In this article, we'll examine the psychological and physical properties of fear, find out what causes a fear response and look at some ways you can defeat it.

What is Fear?

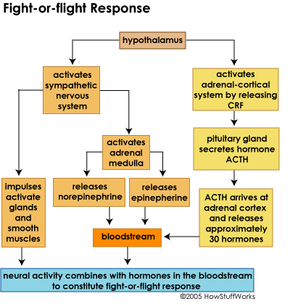

Fear is a chain reaction in the brain that starts with a stressful stimulus and ends with the release of chemicals that cause a racing heart, fast breathing and energized muscles, among other things, also known as the fight-or-flight response. The stimulus could be a spider, a knife at your throat, an auditorium full of people waiting for you to speak or the sudden thud of your front door against the door frame.

The brain is a profoundly complex organ. More than 100 billion nerve cells comprise an intricate network of communications that is the starting point of everything we sense, think and do. Some of these communications lead to conscious thought and action, while others produce autonomic responses. The fear response is almost entirely autonomic: We don't consciously trigger it or even know what's going on until it has run its course.

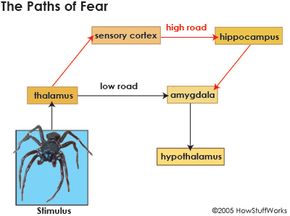

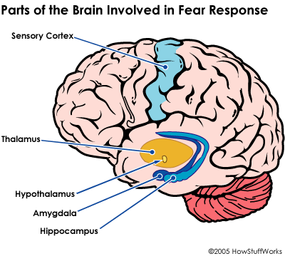

Because cells in the brain are constantly transferring information and triggering responses, there are dozens of areas of the brain at least peripherally involved in fear. But research has discovered that certain parts of the brain play central roles in the process:

- Thalamus - decides where to send incoming sensory data (from eyes, ears, mouth, skin)

- Sensory cortex - interprets sensory data

- Hippocampus - stores and retrieves conscious memories; processes sets of stimuli to establish context

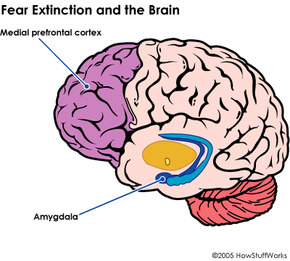

- Amygdala - decodes emotions; determines possible threat; stores fear memories

- Hypothalamus - activates "fight or flight" response

The process of creating fear begins with a scary stimulus and ends with the fight-or-flight response. But there are at least two paths between the start and the end of the process. In the next section, we'll take a closer look at how fear is created.