Key Takeaways

- Lightning can strike the same place multiple times, with tall structures like the Empire State Building being struck many times each year.

- You are at risk of being struck by lightning even when it's not raining, with phenomena like "Bolts from the Blue" striking from clear skies miles away from a storm.

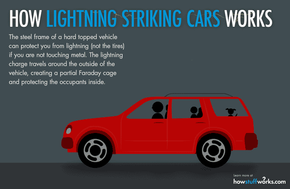

- Rubber tires do not protect you from lightning strikes. Instead, it's the car's metal body that acts as a Faraday cage, and safety in buildings requires avoiding electrical conductors and using surge protectors.

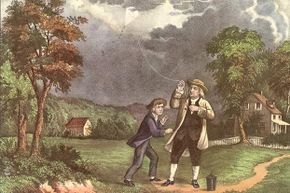

Way back in 1752, Benjamin Franklin set out to discover the truth about lightning. The inventor, statesman and bon vivant fashioned a kite from a large silk handkerchief stretched across a pair of sticks and directed via a metal wire attached to a piece of twine with a key dangling from it. He then went on a kite-flying expedition in the middle of a thunderstorm [sources: History, The Electric Ben Franklin].

Or did he? While the story of how Franklin discovered electricity in the atmosphere has come under question in the two-and-a-half centuries since his little experiment is said to have happened, what we do know is that he helped to greatly improve our understanding of how both lightning and electricity work.

Advertisement

Describing the shock he received when his knuckles touched the key of the kite, Franklin determined that lightning is a natural electric discharge. While this discovery has been hailed as one of the world's great early scientific achievements, there remain some limits on our understanding of why lightning happens, where it strikes and what the right thing to do is when a thunderstorm hits (hint: do not go fly a kite).

The story of Franklin and the kite is just one myth about lightning. Many pieces of wisdom handed down from our parents are now considered out of date or were just plain wrong to begin with. Which are the 10 biggest lightning myths out there? We'll start with one that became a proverb.