Could an examination of the lumps and valleys on your head guide you to the right lover, give clues to the kind of parent you'd be or help determine your career path? Phrenologists in the 19th century thought so, and they convinced hordes of people to pay to have their heads examined.

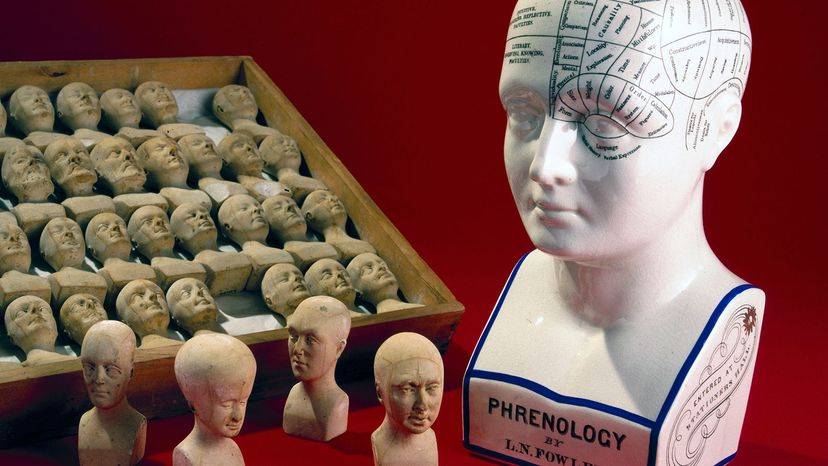

Phrenology, as the practice became known, was a movement during the Victorian era, popularized and sensationalized to the point that phrenology parlors and "automated phrenology machines" popped up across Europe and America. Live events were considered both educational and entertaining, with speakers often conducting onstage head examinations.

Advertisement

Phrenology intrigued people from all walks of life. The middle and working classes were consumed with the idea of that this kind of scientific knowledge was power. Even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were curious enough to have the heads of their children read.

But as popular and entertaining as phrenology was, its heyday was short-lived. By the early 1900s, the so-called science behind phrenology was debunked. Today, it is considered a pseudoscience barely mentioned in "Intro to Psychology" classes. But is there any redeeming value to phrenology?

Well, sort of.

Where Did Phrenology Come From?

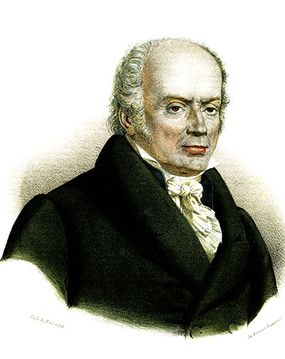

The idea that one's skull could give hints to someone's intelligence and personality first popped into the mind of German physician Franz Joseph Gall in the late 1700s, when he was a medical student. Gall noticed that classmates with larger eyes and more expansive foreheads seemed more adept at memorizing long passages. This, he surmised, suggested that one's emotional characteristics were not dictated by the heart, as was assumed at the time, but from somewhere in the head.

By the 1790s, Gall began to study the localization of mental functions in the brain, believing that certain areas were responsible for psychological activity. Gall further believed that the shape of the skull reflected personality traits and mental abilities that corresponded to the topography of the brain. He called this "science of the head" craniology and, later, after believing the brain to be not one organ but a group of organs, changed the name of his study to organology.

In 1800, Gall teamed up with Johann Christoph Spurzheim to further research this theory. The two worked together for a dozen years before having a falling out. Spurzheim became intrigued with the psychosocial potential of this new science, believing it could empower people to improve themselves. He renamed the practice "phrenology," defined it as "the science of the mind," and set out on a lecture tour to preach the wondrous new concept throughout Britain. It caught on like wildfire, igniting interest in Scottish lawyer George Combe, who in 1820 would establish the Edinburgh Phrenological Society, the first and foremost phrenology group in Great Britain.

In 1832, Spurzheim landed on American soil with the same plan of spreading interest in phrenology, but three months later literally worked himself to death. It proved to be plenty of time to gin up the support of the entrepreneurial Fowler brothers (Orson Squire and Lorenzo Niles Fowler) and their business associate Samuel Roberts Wells.

The Fowlers, including Lorenzo's wife Lydia, became notable phrenologists in the U.S. They toured the country to share the "truth about phrenology." In 1838, the Fowlers opened an office in Philadelphia called the Phrenological Museum, where they began publishing the American Phrenological Journal. The Fowler's New York office was known as the Phrenological Cabinet and became one of the most visited sites in town.

By the mid-1800s, interest in phrenology was at an all-time high. People scrambled to attend phrenology lectures, have their heads read and even style their hair in order to show off their most pronounced head bumps. Practical applications grew to include using phrenology readings to defend or treat convicted criminals, discern one's love of children and determine the compatibility of two people in marriage.

Advertisement