Back in 2006, to the puzzlement of many in the nonscientific public and some astronomers as well, the International Astronomical Union decided to demote Pluto from its status as a full-fledged planet in our solar system. Instead, the IAU decided, what had been considered the most distant of the nine planets actually belonged in the new category of dwarf planet, a category that also included Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

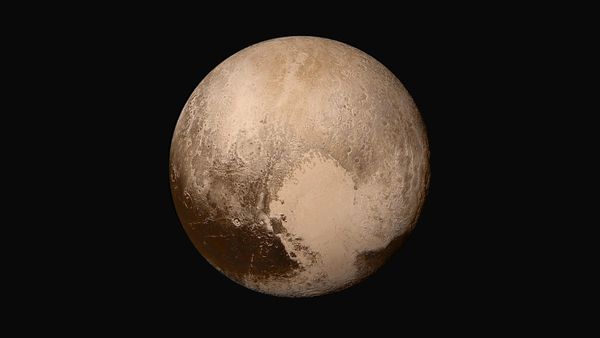

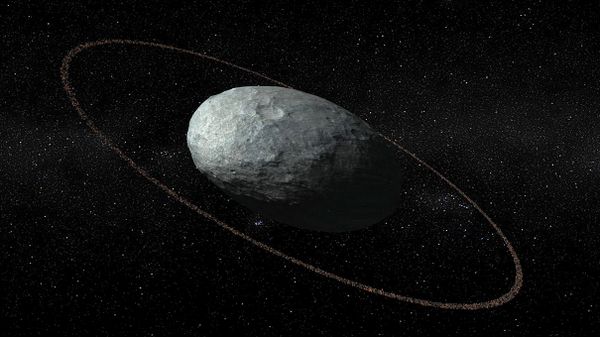

The reasoning, as explained in the IAU's Resolution B6, was that Pluto only had two of what the IAU decided were the three characteristics of a planet — that it is in orbit around the sun, that it has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces and give it a nearly spherical shape, and that it has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit of other objects, meaning that it's either collided with, captured or driven away smaller objects nearby. Pluto flunked the IAU's last test, because it shares its orbit with thousands of smaller icy objects in the Kuiper Belt, a region that's between 2.5 and 4.5 billion miles (4.5 and 7.4 billion kilometers) away from the sun.

Advertisement

The IAU's decision, which was voted on by a very small percentage of the world's astronomers and planetary scientists, was a controversial one. After a debate among scientists sponsored by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in 2014, the majority of the nonexpert audience voted for a simpler definition of planet — basically, that it had to be spherical and orbit around a star or the remnants of one — that included Pluto, according to an article on the center's website.

And now, contention may well flare up again, thanks to a paper preprinted online in the February 2019 issue of the scientific journal Icarus, authored by University of Central Florida planetary physicist Philip Metzger, Planetary Science Institute director Mark Sykes, planetary scientist Alan Stern, who led NASA's New Horizons space probe mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, and Johns Hopkins University planetary geomorphologist Kirby Runyon. They analyzed more than two centuries' worth of studies published by scientists, and found that, with the exception of a paper published in 1802 by British astronomer Sir William Herschel, nobody talked about non-sharing of an orbit as a criterion for distinguishing planets from asteroids. To the contrary, the researchers found that scientists routinely described asteroids as planets until the 1950s, "on the basis of new data showing asteroids' geophysical differences from large, gravitationally rounded planets."

"We therefore conclude that the argument made during the IAU planet definition controversy, that planet-sized Kuiper Belt Objects should be classified as non-planets because they share orbits, is arbitrary and not based on historical precedent," they wrote.

"If you were to abstract a definition of planet" from how it is used in the scientific literature it would be something like, 'Planets are objects that are large enough to be round' — with no consideration of where they are or what they orbit," Sykes explains in an email.

Advertisement