Advertisement

In the lead-up to the 2008 Summer Olympics, the People's Republic of China garnered a lot of press for all its housecleaning efforts. The country made strides toward cleaning up pollution, revamping public transportation and generally tidying up the city of Beijing. After all, the event promised to be the biggest party of the year, with the entire world invited to tune in. Authorities deterred potential party crashers by making it harder to visit the city and, yes, even requiring the visiting Luchadores to carry permits for their trademark Mexican wrestling masks.

If you've ever thrown a party, you too may have fretted over every detail concerning the evening. Will the guests think you're cheap if you don't use the good china? Will your kids be on their best behavior, or should you banish them to their rooms? Chinese officials faced similar worries heading into the summer games, only they took their micro planning to unheard of levels. See, the Aug. 8 opening ceremony happened to fall during a traditionally wet season for Beijing. To avoid any crimp in their plans, they decided to shoot down any cloud that looked as though it might try to enter the city uninvited.

That may sound extreme, but Chinese authorities didn't become such meteorological control freaks overnight. Chinese research into weather control dates back to 1958. Forty years later, the government-run Weather Modification Program launches thousands of specially designed rockets and artillery shells into the sky every year in an attempt to manipulate weather conditions.

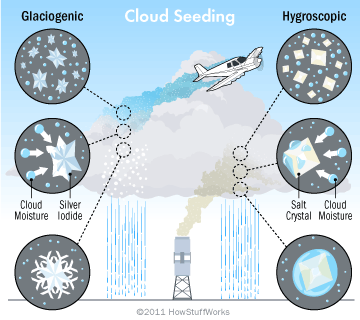

Run by the Weather Modification Department, a division of the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, the program employs and trains 32,000 to 35,000 people across China, some of them farmers, who are paid to handle anti-aircraft guns and rocket launchers [source: Aiyar]. These heavy-duty weapons launch pellets containing silver iodide into clouds. Silver iodide is thought to concentrate moisture and cause rain, a process known as cloud seeding. China has invested heavily in this technology, using more than 12,000 anti-aircraft guns and rocket launchers in addition to about 30 planes [source: Aiyar].

With a population of more than 1.3 billion, China requires vast amounts of water. The government practices cloud seeding to try to produce rain for farmers, stave off drought, clear away air pollution and smog, fill water basins and, of course, produce a picture-perfect opening Olympic ceremony.

Were Chinese authorities successful in keeping their atmospheric gatecrashers at bay? And how does cloud seeding actually work? Read on to find out.

Advertisement