Key Takeaways

- An international team aims to drill through the Earth's crust into the mantle using the drilling vessel Chikyu.

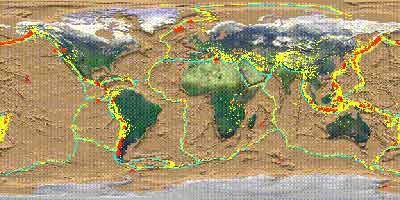

- Reaching the mantle, which makes up 83 percent of Earth's volume, would provide invaluable insights into Earth's formation and plate tectonics.

- Despite previous failed attempts, advances in drilling technology and a better understanding of the ocean crust may enable success in reaching the mantle, though extreme temperatures and pressure pose significant challenges.

If your family took you on a vacation to the seashore when you were a small child, you probably remember the exhilarating feeling of digging into the wet sand with a plastic shovel. As the hole got bigger and deeper, you naturally wondered what would happen if you just kept digging and digging. How deep could you get? Would you really eventually pop up out of the ground somewhere in China, as your big sister or brother tried to get you to believe? Unfortunately, you never got to find out, because just as you were starting to make some real progress, it was time to pack up the beach umbrella, and go get an ice-cream cone and take a 10-cent ride on the mechanical pony on the boardwalk. But still, somewhere in the back of your mind, you've kept wondering about what would happen if someone dug a really, really deep hole.

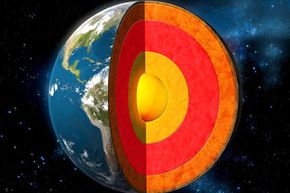

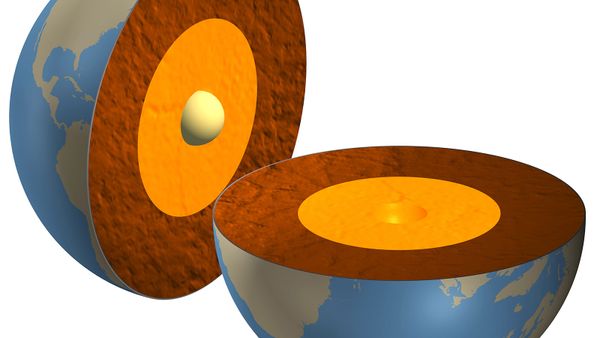

Well, you may not have to wonder any more, if an international team of scientists who call themselves the 2012 MoHole To the Mantle project succeed in their quest. They're counting upon international support for a $1 billion effort in which a Japanese deep-sea drilling vessel, the Chikyu, would burrow into the bottom of the Pacific Ocean to dig deeper than anyone has ever gone before. The plan is to go right through the Earth's crust, the rocky top layer of the planet, which is 18 to 37 miles (30 to 60 kilometers) thick on land, but as little as 3 miles (5-kilometers) thick at its thinnest spots on the ocean floor [source: Osman]. If the Chikyu's drill rig breaks through a transitional boundary called the Moho, it would reach the Earth's mantle, the mysterious 1,740-mile (2,900-kilometer) thick layer between the crust and the planet's hot, molten core [sources: USGS, ScienceDaily].

Advertisement

Unlike your childhood fantasy, the scientists don't have any ambitions of boring a tunnel all the way through the planet. That probably isn't even possible, since the enormous heat and pressure inside the Earth would make crawling down such a passageway impossible, even if it somehow didn't collapse. But just reaching the mantle, a layer about which we know relatively little, and retrieving a sample would be a scientific achievement of such a magnitude that some have called it geology's version of the moon landing. In this article, we'll explain the difficulty of digging such a deep hole, and what we might gain from it.

Advertisement