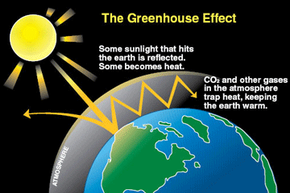

When the sun's rays hit the Earth's atmosphere and the surface of the Earth, approximately 70 percent of the energy stays on the planet, absorbed by land, oceans, plants and other things. The other 30 percent is reflected into space by clouds, snow fields and other reflective surfaces [source: NASA].

But even the 70 percent that gets through doesn't stay on Earth forever (otherwise, the Earth would become a blazing fireball). The things around the planet that absorb the sun's heat eventually radiate a portion of that heat (radiation) back out at a different wavelength, like your car seats and dashboard do.

This absorption-radiation process keeps the Earth in radiative equilibrium: The sun's radiation continually strikes the Earth, warming it; the warm Earth emits some of that radiation back into space, cooling itself. The more solar radiation the Earth absorbs, the more radiation it releases.

Some of that released radiation makes it into space, and the rest of it ends up getting reflected back down to Earth when it hits certain things in the atmosphere, such as carbon dioxide, methane gas and water vapor — the car windows.

The heat that doesn't make it out through Earth's atmosphere keeps the planet warmer than it is in outer space, because more energy is coming in through the atmosphere than is going out. This is the greenhouse effect that keeps the Earth warm.

If there were no greenhouse effect on Earth, our planet would probably look a lot like Mars. Mars doesn't have a thick enough atmosphere to reflect much heat back to the planet, so it gets very cold there.

So the greenhouse effect is actually a good thing — and as with most good things, moderation is key.

The reason we often associate the greenhouse effect with environmental damage is that since the Industrial Revolution, the greenhouse effect has fallen out of balance: Earth's atmosphere is trapping too much heat.

Greenhousing Mars

Some scientists have suggested that we could terraform the surface of Mars by sending "factories" that would spew water vapor, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the air. If enough greenhouse gas emissions could be generated, the atmosphere might start to thicken enough to retain more heat and allow plants to live on the surface.

Once plants spread across Mars, they would start producing oxygen. After a few hundred or thousand years, Mars might actually have an environment that humans could simply walk around in — all thanks to the greenhouse effect.