One of the amazing things about our universe is that nothing really goes to waste. For instance, you — the incredible masterwork that you are — happen to be composed of the trash that exploded out of a supernova. In every nook and cranny of the cosmos, the universe is reorganizing and reusing. It is The Great Recycler.

This planet recycles everything — water, carbon, nutrients of all kinds. So, it stands to reason that we'd be really good at recycling stuff here on Earth. But we humans are only so-so recyclers. Take plastic: We do a great job of digging up ancient deposits of carbon in order to make the stuff — recycling, sort of! — but since the 1940s, we've manufactured mind-boggling amounts of a material that will likely hang out in the environment for centuries, killing wildlife and leaching toxic chemicals. Less than 10 percent of that is typically recycled.

Advertisement

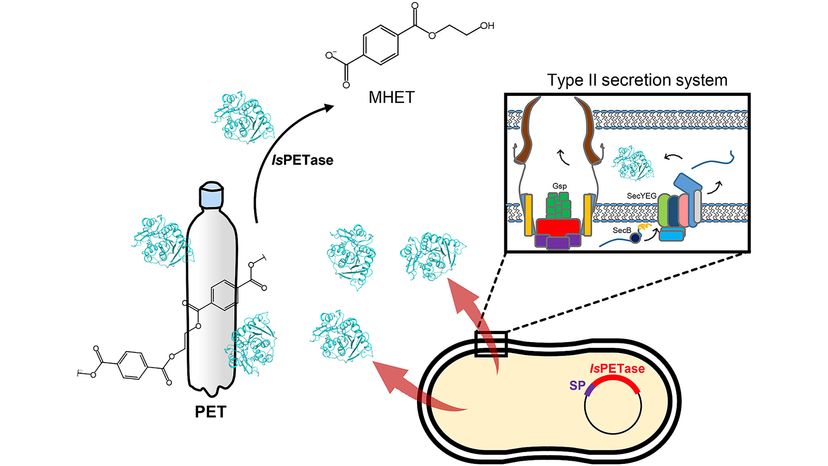

In 2016, a Japanese research team discovered a bacteria (Ideonella sakaiensis) making some inroads into plastics recycling where humans were failing. Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) plastics are everywhere — most notably in plastic soda and water bottles — and the bonds that hold it together are very strong, so it was something of a surprise when a colony of these bacteria were discovered in a Japanese landfill.

In the April 17, 2018 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, an international group of researchers reported on the enzyme known as PETase produced by this bacteria. They found that the PETase enzyme digests PET. However, PETase is only part of the equation. Researchers also needed to understand the structure of the second enzyme, MHETase.

That's where biochemist and structural biologist Dr. Gert Weber and his team from the joint Protein Crystallography research group at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin and Freie Universität Berlin come in. Weber and his team determined that MHETase not only binds to PET, it also decomposes it. Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications April 2019 issue.

We talked to Weber via email and he explained how it happens: "Both [PETase and MHET] belong to an enzyme class, termed hydrolases. They break down ester bonds of the commonly used plastic PET so that the building blocks that we need for a re-synthesis of the polymer are released," he explains.

"PETase is only half the size of MHETase and breaks down the polymer (PET) to smaller pieces, called MHET (which consists of the two building blocks of PET, ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid). MHETase then splits MHET to yield the very two substances which are needed for a new round of polymer synthesis, ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid," he adds

So what does that mean? Well these two bacterial enzymes specifically degrade PET plastics. Sounds like they could potentially be a solution to Earth's massive waste problem, right? Not so fast, Weber says. The issue is they're slow and inefficient. "Both enzymes come from bacteria," he says. Since PET is only about 75 years old, both enzymes have undergone a rapid evolution and are far from perfect.

Weber says he believes the plastic-eating enzymes will eventually improve so they could work in some type of environmental capacity. But it will be limited. "Traditional recycling methods of PET (which amounts to about 18% of all plastics) have many disadvantages," he explains. "Intensive pre-sorting is required and they are energy-intensive and rely on crude oil to a large degree [to create]. Enzymes like PETase and MHETase break down PET to its building blocks, which can then be purified ... These pure building blocks ... can then be used for a new round of PET synthesis. This can be done over an unlimited number of cycles, with a minimum carbon loss, requiring low amounts of energy and nearly free of crude oil consumption."

So essentially, if it works, it could create a closed production and recovery cycle for PET plastic that's totally sustainable. But the news isn't all good.

"In the environment, plastics are either disposed in a fragmented form already, or [they] fragment over time (microplastics)," Gerber says. "The smaller the fragments, the harder they are to remove them from the environment. The distribution and fragmentation of plastics is too pervasive to address it with any measure. It may well be that nature (as seen with PETase and MHETase) still finds solutions to other polymer types with different enzymes." His advice: Cease production of the PET plastics as soon as possible.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Advertisement