Pasteur's Experiment

The steps of Pasteur's experiment are outlined below:

First, Pasteur prepared a nutrient broth similar to the broth one would use in soup.

Advertisement

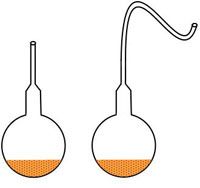

Next, he placed equal amounts of the broth into two long-necked flasks. He left one flask with a straight neck. The other he bent to form an "S" shape.

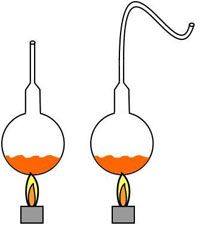

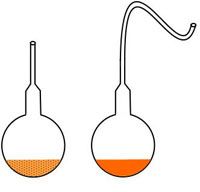

Then he boiled the broth in each flask to kill any living matter in the liquid. The sterile broths were then left to sit, at room temperature and exposed to the air, in their open-mouthed flasks.

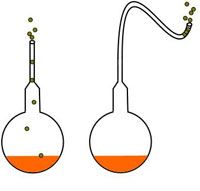

After several weeks, Pasteur observed that the broth in the straight-neck flask was discolored and cloudy, while the broth in the curved-neck flask had not changed.

He concluded that germs in the air were able to fall unobstructed down the straight-necked flask and contaminate the broth. The other flask, however, trapped germs in its curved neck, preventing them from reaching the broth, which never changed color or became cloudy.

If spontaneous generation had been a real phenomenon, Pasteur argued, the broth in the curved-neck flask would have eventually become reinfected because the germs would have spontaneously generated. But the curved-neck flask never became infected, indicating that the germs could only come from other germs.

Pasteur's experiment has all of the hallmarks of modern scientific inquiry. It begins with a hypothesis and it tests that hypothesis using a carefully controlled experiment. This same process — based on the same logical sequence of steps — has been employed by scientists for nearly 150 years. Over time, these steps have evolved into an idealized methodology that we now know as the scientific method. After several weeks, Pasteur observed that the broth in the straight-neck flask was discolored and cloudy, while the broth in the curved-neck flask had not changed.

Let's look more closely at these steps.