After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Russian airstrikes began devastating Ukraine's cities, killing scores of civilians in the process. That led Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to call upon the U.S. and its NATO allies, who already were supplying Ukrainian defenders with both Stinger and Patriot missiles and other assistance, to go a step further. Zelensky repeatedly called upon them to use their air forces to prevent Russian aircraft from entering Ukraine's airspace.

"We repeat every day: 'close the sky over Ukraine!'" Zelensky implored in a video. "Close for all Russian missiles, Russian combat aircraft, for all these terrorists. Make a humanitarian air zone."

Advertisement

What Zelensky sought is something called a no-fly zone, known in global security lingo as an NFZ, a concept invented in the early 1990s. In a no-fly zone, a military power or alliance stops an attack on another nation by making its airspace off-limits to the aggressor.

A no-fly zone doesn't necessarily have to cover an entire country. Instead, it might only cover a portion where the fighting is occurring. But either way, a no-fly zone must be enforced by the threat of force. The nation or nations imposing the no-fly zone must deploy surveillance aircraft to monitor the airspace, as well as fighters to deter — and if necessary — shoot down any hostile aircraft that enter the space.

Additionally, creating an effective no-fly zone may also require destroying or disabling any ground-based anti-aircraft systems that the aggressor country possesses, so that they can't be used to attack the aircraft enforcing the ban [sources: Brooke-Holland and Butchard; Ramzy].

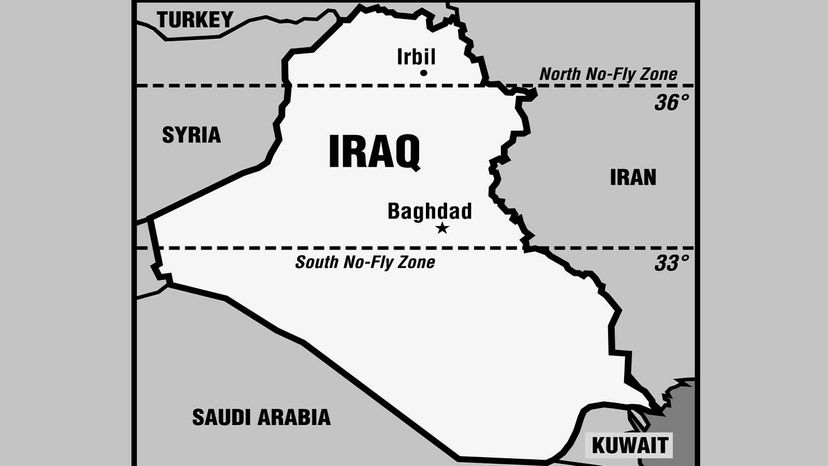

No-fly zones have only been utilized three times in history — in parts of Iraq, following the 1991 Gulf War; in Bosnia in 1992; and Libya in 2011 [source: Brooke-Holland and Butchard]. Those crises were situations in which the U.S. and NATO used their superior air power to stymie authoritarian rulers of less powerful countries from brutally suppressing rebellions and terrorizing civilian populations.

But in Ukraine, the U.S. and NATO have so far resisted imposing a no-fly zone out of concerns that it would draw them into an armed showdown with Russia, whose increasingly irrational leader, Vladimir Putin, might resort to using nuclear weapons [source: CNN].

In this article, we'll look at what it requires to impose a no-fly zone, and whether no-fly zones are effective at their intended goal. But first, let's discuss when, where and why no-fly zones are needed.

Advertisement