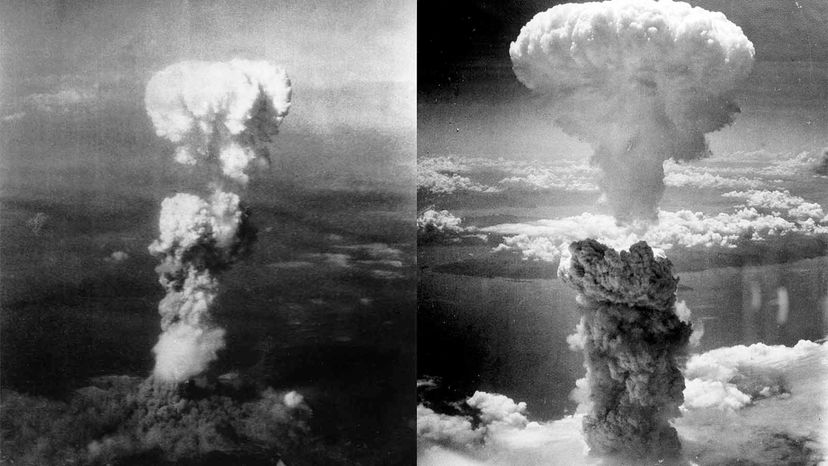

The first nuclear bomb meant to kill humans exploded over Hiroshima, Japan, Aug. 6, 1945. Three days later, a second bomb detonated over Nagasaki. The death toll for the two bomb blasts — an estimated 214,000 people — and destruction wrought by these weapons was unprecedented in the history of warfare [source: Icanw.org]

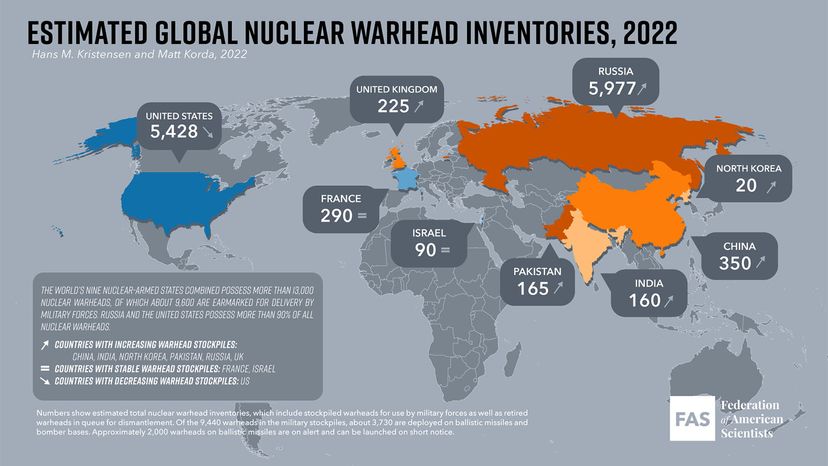

At the end of World War II, the U.S. was the world's only superpower that possessed nuclear capabilities. But that didn't last long. The Soviet Union, with the help of a network of spies who stole American nuclear secrets, successfully tested their own atomic bomb in 1949 as well [sources: Icanw.org, Holmes].

Advertisement

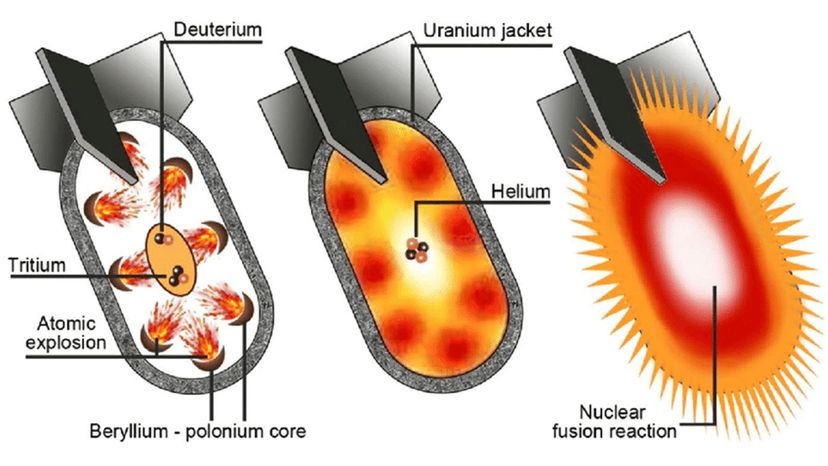

As the U.S. and the Soviets slipped into a decadeslong period of animosity that became known as the Cold War, both nations developed an even more powerful nuclear weapon — the hydrogen bomb — and built arsenals of warheads. Both countries augmented their fleets of strategic bombers with land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of reaching one another's cities from thousands of miles away. Submarines were equipped with nuclear missiles as well, making it even easier to launch a devastating attack [sources: Locker, Dillin].

Other nations — the United Kingdom, France, China and Israel — all had nuclear weapons by the late '60s [source: Icanw.org].

The nuclear bomb loomed over everyone and everything. Schools conducted nuclear air raid drills. Governments built fallout shelters. Homeowners dug bunkers in their backyards. Eventually, the nuclear powers became frozen in a standoff. Both had a strategy of mutual assured destruction — basically that even if one nation launched a successful sneak attack that killed millions and wreaked widespread devastation, the other nation still would have enough weapons left to counterattack and inflict an equally brutal retribution.

That grisly threat deterred them from utilizing nukes against one another, but even so, the fear of a cataclysmic nuclear war remained. During the 1970s and '80s, tensions continued. Under President Ronald Reagan, the U.S. pursued a strategy of developing anti-missile defense technology — dubbed "Star Wars" by skeptics — that was intended to protect the U.S. from attack, but also might have enabled the U.S. to strike first with impunity. By late in the decade, as the Soviet Union began to teeter economically, Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev were working in earnest toward nuclear arms limitation.

In 1991, Reagan's successor, George H.W. Bush, and Gorbachev signed an even more important treaty, START I, and agreed to major reductions in their arsenals. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Bush and Boris Yeltsin, president of the new Russian Federation, signed another treaty, START II, in 1992, which cut the number of warheads and missiles even more [source: U.S. State Department].

But the specter of the nuclear bomb never really went away. In the early 2000s, the U.S. invaded Iraq and toppled its dictator, Saddam Hussein, in part due to a fear that he was trying to develop a nuclear weapon. It turned out, though that he had abandoned those secret efforts [source: Zoroya]. By then Pakistan had tested its first nuclear weapon in 1998 [source: armscontrolcenter.org].

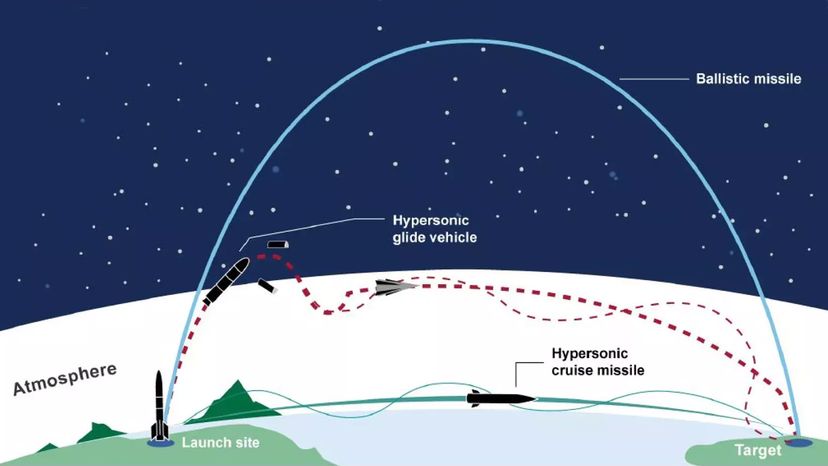

But another totalitarian country, North Korea, succeeded where Saddam had failed. In 2009, the North Koreans successfully tested a nuclear weapon as powerful as the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The underground explosion was so significant that it created an earthquake with a magnitude of 4.5 [source: McCurry]. And by the 2020s, increasing tensions between Russia and western nations, coupled with the prospect of a new generation of hypersonic missiles capable of evading early-warning systems to deliver nuclear warheads, raised the prospect of a frightening new nuclear arms race [source: Bluth].

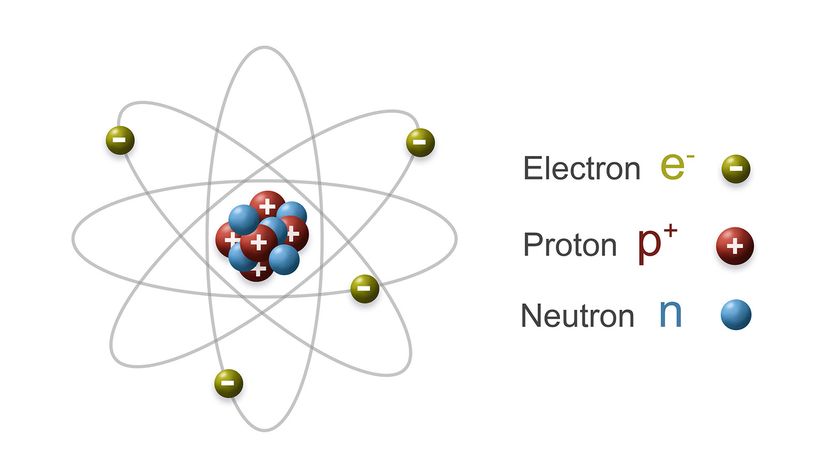

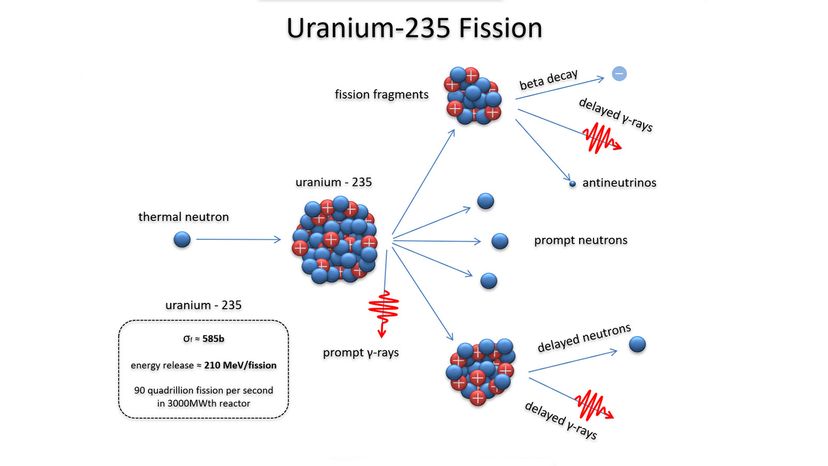

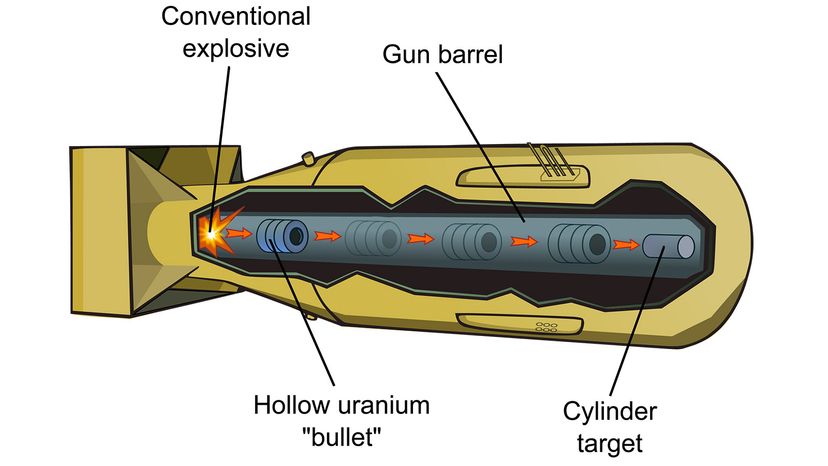

While the political landscape of nuclear warfare has changed considerably over the years, the science of the weapon itself — the atomic processes that unleash all of that fury — have been known since the time of Einstein. This article will review how nuclear bombs work, including how they're built and deployed. Up first is a quick review of atomic structure and radioactivity.

Advertisement