Ever since humans acknowledged the enormity of the universe, we have intuited that life must exist somewhere, either in our galaxy or some galaxy far, far away. If the universe contains billions of galaxies, and if each galaxy contains billions of stars, and if a fraction of those stars have Earth-like planets, then hundreds -- maybe even thousands -- of alien civilizations must exist across the cosmos. Right?

For a while, science contented itself with the logic alone. Then, in 1995, astronomers located the first planets outside our solar system. Since then, they've detected nearly 300 of these extra-solar planets. Although most are large, hot planets similar to Jupiter (which is why they're easier to find), smaller, Earth-like planets are beginning to reveal themselves. In June 2008, European astronomers found three planets, all a little larger than Earth, orbiting a star 42 light-years away [source: Vastag].

Advertisement

These discoveries have served as an affirmation for those involved with the search for extraterrestrial intelligent life, or SETI. Harvard physicist and SETI leader Paul Horowitz boldly stated in a 1996 interview with TIME Magazine, "Intelligent life in the universe? Guaranteed. Intelligent life in our galaxy? So overwhelmingly likely that I'd give you almost any odds you'd like."

And yet his enthusiasm must be tempered by what scientists call the Fermi Paradox. This paradox, first articulated by nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi in 1950, asks the following questions: If extraterrestrials are so common, why haven't they visited? Why haven't they communicated with us? Or, finally, why haven't they left behind some residue of their existence, such as heat or light or some other electromagnetic offal?

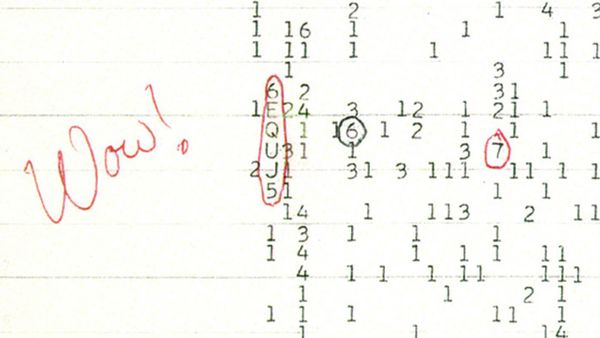

Perhaps extraterrestrial life isn't so common after all. Or perhaps extraterrestrial life that gives rise to advanced civilizations isn't so common. If only astronomers could quantify those odds. If only they had a formula that accounted for all of the right variables related to extraterrestrial life. As it turns out, they do. In 1961, as a way to help convene the first serious conference on SETI, radio astronomer Frank Drake presented a formula, now known as the Drake Equation, that estimates the number of potential intelligent civilizations in our galaxy. The formula has generated much controversy, mainly because it leads to widely variable results. And yet it remains our one best way to quantify just how many extraterrestrials are out there trying to communicate.

Let's take a closer look at the equation and its implications.

Advertisement