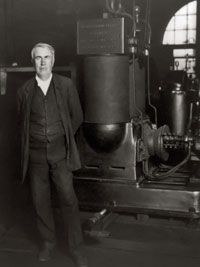

When you flip a switch and a lamp bathes the room in light, you probably don't give much thought to how it works -- or to the people who made it all possible. If you were forced to acknowledge the genius behind the lamp, you might name Thomas Alva Edison, the inventor of the incandescent light bulb. But just as influential -- perhaps more so -- was a visionary named Nikola Tesla.

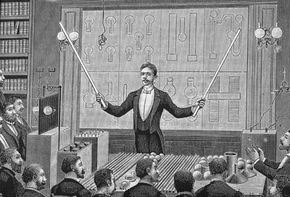

Tesla arrived in the United States in 1884, at the age of 28, and by 1887 had filed for a series of patents that described everything necessary to generate electricity using alternating current, or AC. To understand the significance of these inventions, you have to understand what the field of electrical generation was like at the end of the 19th century. It was a war of currents -- with Tesla acting as one general and Edison acting as the opposing general.

Advertisement

The State of Electricity in 1885

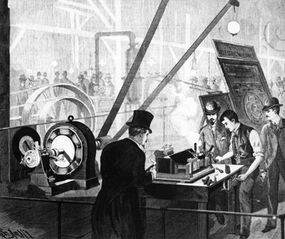

Edison unveiled his electric incandescent lamp to the public in January 1880. Soon thereafter, his newly devised power system was installed in the First District of New York City. When Edison flipped the switch during a public demonstration of the system in 1881, electric lights twinkled on -- and unleashed an unprecedented demand for this brand-new technology. Although Edison's early installations called for underground wiring, demand was so great that parts of the city received their electricity on exposed wires hung from wooden crossbeams. By 1885, avoiding electrical hazards had become an everyday part of city life, so much so that Brooklyn named its baseball team the Dodgers because its residents commonly dodged shocks from electrically powered trolley tracks [source: PBS].

The Edison system used direct current, or DC. Direct current always flows in one direction and is created by DC generators. Edison was a staunch supporter of DC, but it had limitations. The biggest was the fact that DC was difficult to transmit economically over long distances. Edison knew that alternating current didn't have this limitation, yet he didn't think AC a feasible solution for commercial power systems. Elihu Thomson, one of the principals of Thomson-Houston and a competitor of Edison, believed otherwise. In 1885, Thomson sketched a basic AC system that relied on high-voltage transmission lines to carry power far from where it was generated. Thomson's sketch also indicated the need for a technology to step down the voltage at the point of use. Known as a transformer, this technology would not be fully developed for commercial use until Westinghouse Electric Company did so in 1886.

Even with the development of the transformer and several successful tests of AC power systems, there was an important missing link. That link was the AC motor. On the next page, we'll look at how Tesla made the connection.

Advertisement