The name "cinnabar" might make you think this mineral has something to do with cinnamon. But in fact, the word is derived from the Arabic word zinjafr and the Persian word zinjirfrah, which means "dragon's blood." This mineral is certainly blood red, but from dragons, it is not! Cinnabar is born in the shallow veins of blazing volcanic rock. It has historically been used as a pigment called vermilion for millennia, but it's also known for use in traditional medicines and as the primary mineral ore of mercury, a highly toxic chemical element.

Cinnabar is also known as mercury sulfide (HgS), the primary ore of mercury and the same silver liquid in oral thermometers that parents used to check kids' temperatures. In the early 2000s, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) phased them out in place of safer alternatives.

Advertisement

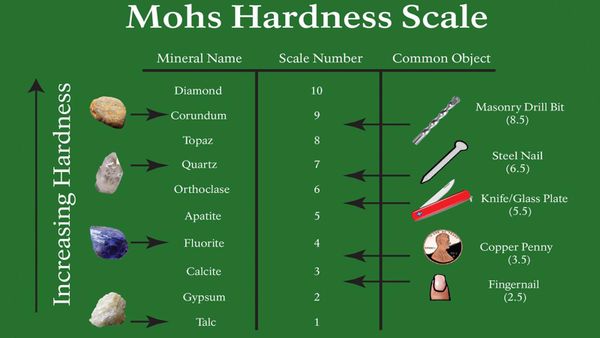

"Cinnabar occurs in near-surface, shallow veins [of volcanic rock], making it easy to mine," says Terri Ottaway, museum curator at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA). "It's crushed and then roasted to extract the mercury." Some mines have been in use since Roman times, Ottaway says, like those in Almadén, Spain. It's also mined around the world in Peru, Italy and the U.S. It registers 2 to 2.5 on the Mohs hardness scale. Today, cinnabar is mainly mined as a source of elemental mercury, but historically cinnabar was a valuable pigment in cultures worldwide because of its color.

Advertisement