When those of us in the developed world think of a global threat, we usually imagine some shadowy terrorist organization or insurgency in politically unstable areas. We generally don't give the sparkling glass of water next to us the side eye.

But according to the United Nations, dirty water is killing more people than war -- or violence in general [source: Pflanz]. And keep in mind that for many people simply getting water is a struggle [source: UN Water]. According to the 2010 World Health Organization and UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), 780 million people do not use improved sources of drinking water [source: JMP 2012]. (The JMP defines an improved source as "one that, through technological intervention, increases the likelihood that it provides safe water" [source: JMP 2012].) To make matters worse, purifying water to make it drinkable can be a time-consuming, expensive process.

Advertisement

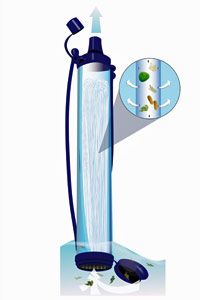

The challenge is to create a safe, effective way to treat the drinking water of the poorest nations -- without an enormous financial burden. Swiss company Vestergaard Frandsen believes that its product, LifeStraw -- as well as a unique distribution method -- may be a solution. In the next few pages, we'll explore how LifeStraw works, as well as other methods to get clean water to those who need it.

But as you read, keep in mind that unclean water is no small burden on the global population. About half of the world's poor suffer from diseases caused by the water they consume, and approximately 6,000 people die each day from illnesses that access to clean water could have prevented [source: United Nations]. Cholera, typhoid and enteric fever are all deadly illnesses caused by the consumption of contaminated water. Bacterial or viral contaminants in the water can cause diarrhea and vomiting in humans by releasing toxins into the intestines. Globally, diarrhea is the leading cause of illness and death, and 88 percent of those deaths are due to lack of sanitation facilities, combined with limited access to water for hygiene and unsafe water [source: UN Water].

It's a complicated issue, but -- surprisingly -- the technology to fight it might be quite simple.

Advertisement