Key Takeaways

- The title "first scientist" is difficult to bestow due to the evolution of scientific inquiry, but William Gilbert (1544-1603) is a strong candidate, particularly for his work on magnetism and his influence on Galileo Galilei.

- Gilbert's book "De Magnete" detailed experiments that could be replicated to verify results, a hallmark of the scientific method, and he was the first to explain the Earth as a magnetic entity, influencing future scientific exploration.

- Despite the term "scientist" being coined in 1834, figures like Gilbert, who embraced experimentation, observation and the dismissal of mysticism, embody the essence of modern scientific inquiry, setting the stage for the methodology and mindset that define science today.

The word "scientist" entered the English language in 1834. That's when Cambridge University historian and philosopher William Whewell coined the term to describe someone who studies the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment. You could make the argument, then, that the first modern scientist was someone like Charles Darwin or Michael Faraday, two iconic figures who also happened to be Whewell's contemporaries. But even if the term didn't exist before the 1830s, people who embodied its principles did.

To find the very first scientist, we must travel back in time even further. We could go back to the most ancient of the ancient Greeks, all the way back to Thales of Miletus, who lived from about 624 B.C.E. to about 545 B.C.E. By many accounts, Thales achieved much in both science and mathematics, yet he left no written record and may have been, like Homer, a celebrated figure who received credit for many great achievements but who may never have existed at all.

Advertisement

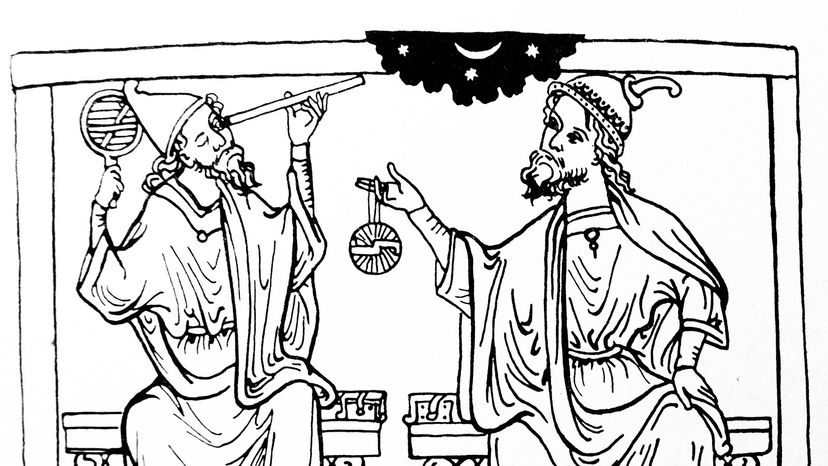

We could consider other ancient Greeks as well, such as Euclid (the father of geometry) or Ptolemy (the misguided astronomer who put Earth at the center of the cosmos). But all of these men, although great thinkers, relied on making arguments instead of running experiments to prove or disprove hypotheses.

Some scholars believe that modern science had its origins in an impressive class of Arabic mathematicians and philosophers working in the Middle East decades before the European Renaissance began. This group included al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Sina, al-Biruni and Ibn al-Haytham. In fact, many experts recognize Ibn al-Haytham, who lived in present-day Iraq between 965 and 1039 C.E., as the first scientist. He invented the pinhole camera, discovered the laws of refraction and studied a number of natural phenomena, such as rainbows and eclipses. And yet it remains unclear whether his scientific method was truly modern or more like Ptolemy and his Greek predecessors. It's also not clear whether he had emerged from the mysticism still prevalent at the time.

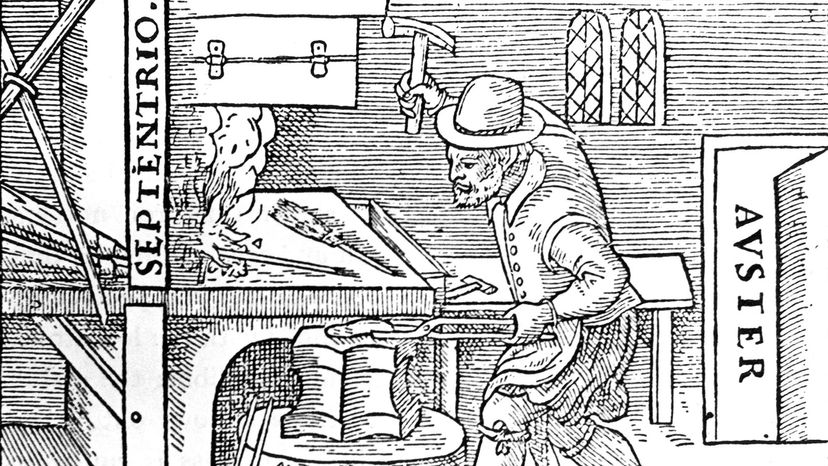

It's almost impossible to determine when the influence of mysticism had faded completely among scientists. What's easier to identify are the characteristics of a modern scientist. According to author Brian Clegg, a modern scientist must recognize the importance of experiment, embrace mathematics as a fundamental tool, consider information without bias and understand the need to communicate. In other words, he or she must be unshackled by religious dogma and willing to observe, react and think objectively. Clearly, many individuals doing scientific work in the 17th century — Christiaan Huygens, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton — satisfied most of these requirements. But to find the first scientist with these characteristics, you have to travel to the Renaissance, to the mid-16th century.

We'll head there next.

Advertisement