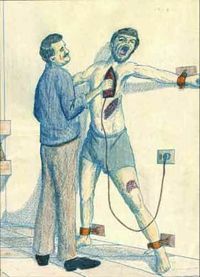

In May 2007, the United States military raided a house outside of Baghdad. From the outside, it seemed to be a normal house; it was the scene inside that was chilling. Five Iraqi nationals had been kept and tortured in the house by al-Qaida. The military also found drawings which it believes are part of a torture manual for al-Qaida operatives. The images include depictions of gruesome acts of torture, like pressing a hot clothing iron against a detainee's skin, removing eyeballs and placing a detainee's head in a vise [source: Department of Defense (CAUTION: GRAPHIC CONTENT)]. Even worse, the tools and instruments necessary to carry out such acts -- like blowtorches and power drills -- were also discovered in the house [source: Fox News].

Advertisement

One may be gripped by panic at the thought of being subjected to any of the methods depicted in the al-Qaida manual; having a limb severed or being hung by your arms behind your back are surely horrifying experiences. To add to the argument against torture, these methods are not generally considered useful. Information gathered from a detainee upon whom an interrogator is inflicting intense physical pain is unlikely to be accurate [source: The New York Times]. In other words, a person who has a hot iron pressed to his or her bare chest is likely to say anything -- factual or not -- just to get the torturer to stop. In 1988, a CIA official testified before a Senate intelligence committee, "Physical abuse or other degrading treatment was rejected, not only because it is wrong, but because it has historically proven to be ineffective" [source: The Baltimore Sun].

How would this government expert know? Because the United States spent decades conducting experiments, field tests and research in a quest to perfect the science of interrogation. Read about the manual that was produced as a result of this research on the next page.

Advertisement