Somewhere between Friday and Saturday, Oct. 1, and 2, 2021, at least 126,000 gallons (572,807 liters) of heavy crude leaked into the waters off the coast of California near Huntington Beach. Boaters began reporting an oily sheen on the surface of the ocean to officials, who then alerted the operators of three offshore platforms and pipelines nearby. All three, which are owned by Amplify Energy Corp., were shut down by Sunday.

"This oil spill constitutes one of the most devastating situations that our community has dealt with in decades," Huntington Beach Mayor Kim Carr said during a news conference Sunday. The ocean and shoreline are closed indefinitely, from Seapoint to Santa Ana.

Advertisement

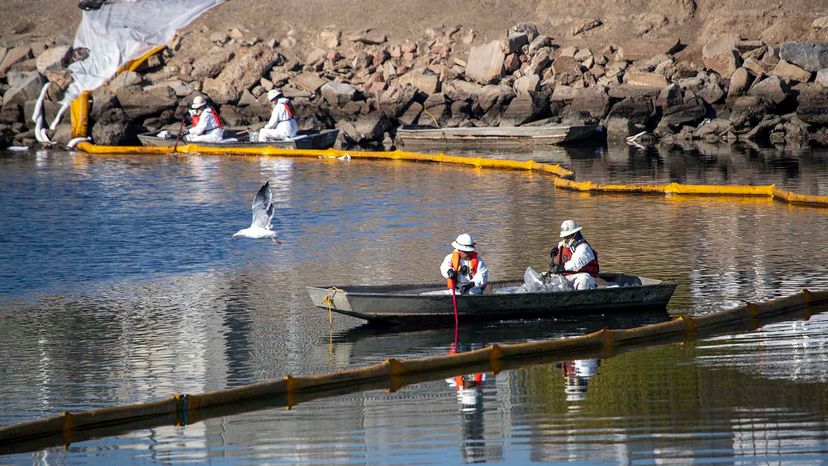

The clean up is being coordinated by the U.S. Coast Guard and the city of Huntington Beach, and includes about 6 miles (9.6 kilometers) along the beaches and wetlands, according to a press statement from Huntington Beach Police Department. But what does that even look like? How do you start to clean up such a massive oil spill?

First let's discuss a bit about crude oil. The world has consumed about 97.4 barrels of oil every day so far in 2021 [source: U.S. Energy Information Administration]. To put that in perspective, there are about 42 gallons (159 liters) in every barrel. In the United States, 90 percent of that oil travels throughout the country via pipeline — eventually. But oil also travels in the U.S. via train car, tanker trucks and massive tanker ships. And where there are pipelines and oil tankers, there are leaks and spills.

But because of stricter penalties and better designs, the number of oil spills has decreased since the oil shipping boom began in the 1960s. However, since the 1969 oil well blowout in Santa Barbara, California, the U.S. has still had at least 44 oil spills with more than 10,000 barrels (420,000 gallons) each. The largest was the 2010 Deepwater Horizon well in the Gulf of Mexico, which killed 11 workers and lasted for more than 87 days. The damaged well dumped 4 million barrels (134 million gallons) of oil into the Gulf, causing $8.8 billion in natural resource damages.

And who could forget the 1989 Exxon Valdez catastrophe? It opened the eyes of the American public to the problem of oil tanker spills. The Valdez ran aground in Prince William Sound in Alaska releasing 11 million gallons of crude oil. As a result, Americans saw countless dead and dying birds and aquatic mammals covered in oil.

Those images of oil-soaked and dead birds sparked the question, "how do you undertake the daunting task of cleaning up millions of gallons of oil?" Agencies responsible for cleaning up oil spills — like the Coast Guard, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Environmental Protection Agency — have some clever and relatively simple methods.

When an oil spill occurs, the oil forms a millimeter-thick slick that floats on the water. The oil eventually spreads out, thinning as it does, until it becomes a widespread sheen on the water. How fast a cleanup crew can reach a spill — along with other factors, like waves, currents and weather — determines what method a team uses to clean a spill.

If a crew can reach a spill within an hour or two, it may choose containment and skimming to clean up the slick. Long, buoyant booms that float on the water and a skirt that hangs below the water can help contain the slick and keep the oil from spreading out. This can make it easier to skim oil from the surface, using boats that suck or scoop the oil from the water and into containment tanks.

Crews also might use sorbents — large sponges that absorb the oil from the water.

An oil spill reached relatively quickly and located away from towns is the easiest to clean up by one of these methods. But rarely do things work out so easily. Oil spills are generally very messy, hazardous and environmentally threatening. Spills often reach shorelines, have time to spread and affect wildlife. In these cases cleanup crews use other measures.

Advertisement