The secret to De Beers' success is a marketing campaign that has permeated our culture --convincing every woman that she should receive a diamond ring from her fiancé and convincing each groom-to-be to pay "two-months salary" for that ring to show how much his love is worth.

Prior to the 1930s, diamond rings were rarely given as engagement rings. Opals, rubies, sapphires and turquoise were deemed much more exotic gems to give as tokens of one's love, according to the book "Twenty Ads that Shook the World" by James B. Twitchell. Twitchell goes on to describe how De Beers changed the world diamond market.

This idea of connecting diamonds to romance was captured in a brilliant ad campaign begun in the 1940s, causing demand for diamonds to increase. Surely you've heard the De Beers advertisement that "A Diamond is Forever." This ad campaign, which was created by the N.W. Ayer advertising agency in 1947, transformed the diamond market. In 2000, Advertising Age magazine named the ad campaign the slogan of the 20th century. De Beers infiltrated Japan with the same ad campaign in the 1960s, and the Japanese public bought into the idea as much as the Americans did.

Later ads by De Beers told consumers to hold onto their family's diamond jewelry and to cherish it as heirlooms -- and it worked. This eliminated the aftermarket for diamonds, which further enabled De Beers to control the market. Without people selling their diamonds back to jewelers or to other people, the demand for new diamonds increased.

There are fewer than 200 people or companies authorized to buy rough diamonds from De Beers. These people are called sightholders, and they purchase the diamonds through the Central Selling Organization (CSO), a subsidiary of De Beers that markets about 70 percent to 80 percent of the world's diamonds. De Beers sells a parcel of rough diamonds to a sightholder, who in turn sends the diamonds to cutting facilities and then to distributors.

Some rough diamonds are sold outside the CSO. These diamonds come from small producers in Australia, Russia and some African countries. The cost of these diamonds is still largely influenced by the prices set by the CSO.

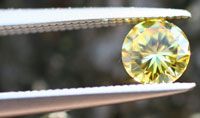

Diamonds are the most coveted of all precious gems, as is witnessed by the extremely high demand for them. While this has not always been the case, diamonds are nonetheless exquisite gems that go through a long, tedious refining process from the time they are pulled from the ground to when you see them in the jewelry store. And, while some of the mystique of diamonds may be gone -- they're just carbon, after all, the diamond will likely continue to be a highly coveted jewel, because, well, "A Diamond is Forever."

But, as the saying goes, beauty often comes at a price. And, sometimes, that price goes beyond the financial realm. In the next section, we'll examine some of the biggest controversies in the diamond industry.