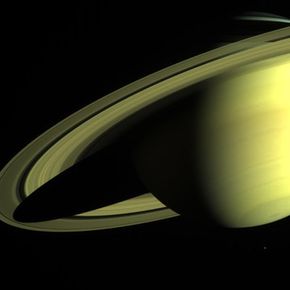

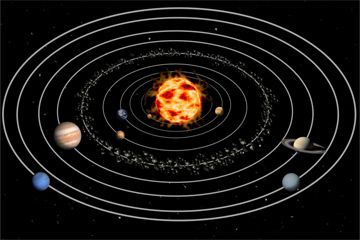

Of all the planets, none seem to capture our fascination like Saturn. The fascination is likely due to the enormous rings that make the second largest planet a standout in our solar system. Although Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune have rings of their own, none are as spectacular as Saturn's.

Saturn's rings are also one of the great mysteries in space. But as our spacecraft edge closer than ever to the rings, we're getting a more complete picture of what they're made of and how they came to exist.

Advertisement

Saturn has seven main rings, each composed of thousands of tiny ringlets. The rings are huge -- the biggest ones spanning 170,000 miles (273,588 km) in diameter. They are, however, proportionately very thin -- only about 650 feet (200 meters) thick. They aren't solid, as they appear from Earth, but are instead made up of floating chunks of water ice, rocks and dust that range in size from specks to enormous, house-sized pieces that orbit Saturn in a ring pattern. As the particles orbit, they collide constantly, shattering the larger pieces.

The rings aren't perfect circles but instead have bends in them caused by the pull of gravity from nearby moons. The rings also contain spokes produced as very fine dust particles floating above the rings get attracted by static electricity and are pulled up above the rings.

The rings are named by letter -- A, B, C, D, E, F and G. They're not in alphabetical order, but are instead in the order in which they were discovered (the actual order, starting from Saturn, is -- D, C, B, A, F, G and E).

A and B are the two brightest rings, and B is the widest and thickest of the seven rings. C is sometimes called the crepe ring, because it's very transparent, and D is barely visible. The F ring is very narrow and held together by two moons -- Pandora and Prometheus -- that sit on either side of the ring. They are called shepherding moons because they control the movement of the particles in the ring.

Farther out is the G ring, and finally the E ring, which is made up of very fine (almost microscopic) particles. The E ring has been most puzzling to scientists, because unlike the other rings, which are believed to be made up of particles shed from nearby moons, E is thought to be made up of ice particles sprayed out of volcanic geysers near the south pole of the moon Enceladus. In between several of the rings are gaps named for the astronomers who have studied Saturn.

But how were the rings formed, and how old could they be? Find out next.

Advertisement