Saber Teeth

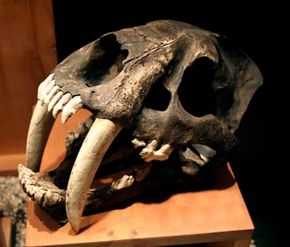

Naturally, the saber-toothed cat is known for its distinctive teeth -- two very long canines that extended well past the lower jaw. These saber teeth evolved to be twice as thick from front to back as from side to side, so they resembled very thick, somewhat curved knife blades. In Smilodon fatalis, adults' saber teeth could measure up to 7 inches (18 centimeters) long. That's about as long as the average man's hand from the wrist to the end of the middle finger.

But the cats' teeth weren't always so big. The "saber-toothed tiger" had deciduous baby teeth, just like people and many other mammals do. The cats lost their baby teeth, including a set of miniature saber canines, before they entered adolescence. In order to reach the necessary length, their adult canines grew at a rate of about 8 millimeters a month for more than 18 months. Today's tigers' teeth grow about this fast, but the canines of saber-toothed cats grew for a longer period of time than tiger teeth do.

The sheer size of these canines can make it seem like eating or attacking prey would be a problem. But saber-toothed cats had the ability to open their mouths very wide to make up for the extreme length of their teeth. Smilodon fatalis could open its mouth up to 120 degrees wide. This let the cats take big bites, although, according to computerized tomography (CT) scans, they used those big bites for soft flesh, not thick bones.

The cats' skulls weren't designed to handle the pressure of biting through bone. They also weren't designed to provide anchors for the amount of muscle needed to hang on to struggling prey for a long time. That's one reason why saber-toothed cats tended to aim for the throat or abdomen instead of the bonier parts of their prey.

Body Length and Killing Behavior

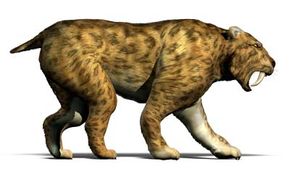

Imagine a bulked-up lion that's lost its tail and been slightly compressed from head to rear and foot to shoulder, and you've got a pretty good idea of what the Smilodon's body was shaped like. Its color is a whole other matter, though. So far, paleontologists haven't found any fossil remains of skin or fur, so there's no solid evidence of their coloring.

However, based on analysis of plant fossils from the last ice age, many paleontologists believe that Smilodon fatalis had the dappled coat of a cheetah or bobcat. This coloring would have helped the cat blend in with the vegetation that was common at the time.

Fossilized bones have also offered some clues about how saber-toothed cats hunted. As previously discussed, due to variations in thickness, the cats' saber teeth were stronger from front to back than side to side. This meant that their teeth easily could have been broken while trying to subdue struggling prey. However, since there aren't many broken saber teeth in the fossil record, it's likely that the cats killed through slashing and stabbing, rather than holding on to struggling prey.