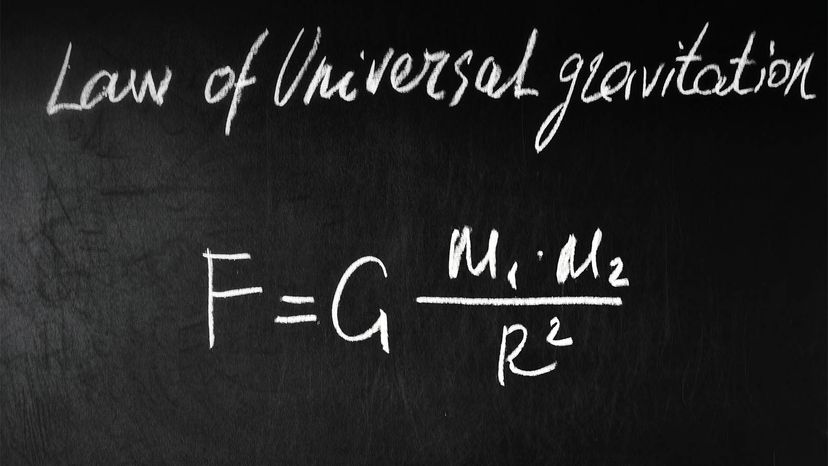

Here on the pale blue dot we call home, gravity is something we all experience every second of every day. And we're far more conscious of it thanks to Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation.

"Gravity is the glue that causes diffuse matter between the stars to slowly collapse and form new hydrogen-fusion machines (aka stars)," says University of Connecticut astrophysicist Cara Battersby. "It is the glue that binds galaxies together and it is responsible for our own Earth orbiting around the sun every year."

Advertisement

Gravity was also the key player in Sir Isaac Newton's famous "apple" story. One day, Newton was hanging out in Lincolnshire, England when he watched an apple fall out of a tree -- or so he claimed. Over the coming years, he'd tell many acquaintances — like Voltaire and biographer William Stukeley — that his great writings about the nature of gravity were inspired by this mundane little event.

Thus, the groundwork was laid for Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation -- central to which is a phenomenon called the universal gravitational constant, aka: "Big G" or just "G." In this article, we'll explore Newton's universal law, the conflicts proposed by Albert Einstein's theory, and gravitational force itself.

Advertisement