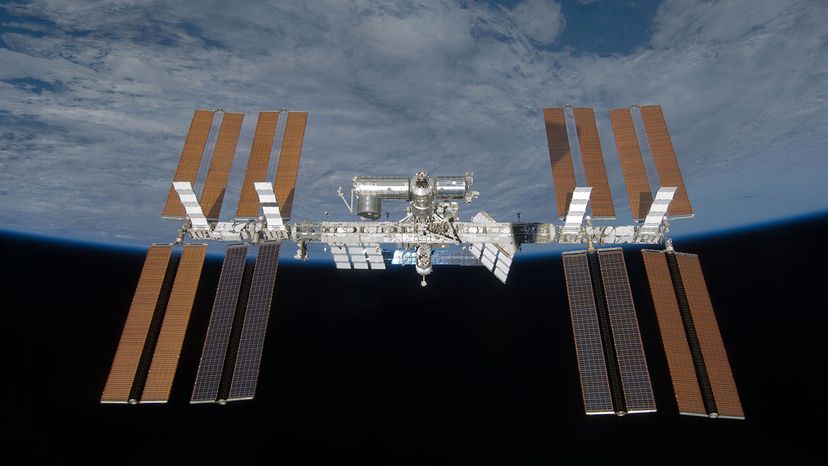

Imagine you wake up in the morning, look out your window and see the vast blue horizon of Earth and the blackness of space. Our world stretches out beneath you. Mountains, lakes and oceans pass by in a beautiful stream of rapidly changing scenery as you orbit the Earth every 90 minutes. Sounds like something unreal out of a science fiction novel, right? For the crews of the International Space Station (ISS), it's a reality.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan proposed a permanently inhabited, government- and industry-supported space station be built by the United States in cooperation with several other countries. Four years later, the U.S. joined forces with Canada, Japan and the European Space Agency (a program then co-managed by the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden and West Germany) to make this station a reality [source: NASA].

Advertisement

The list of participating countries would grow during the 1990s as Russia and Brazil joined the project, although Brazil would eventually cut ties with the ISS in 2007 [source: Gizmodo Brazil].

NASA took the lead in coordinating the ISS's construction, and today the ISS serves as an orbiting laboratory for experiments in life, physical, earth and materials sciences. Its assembly in orbit began in 1998 — and it's been continuously occupied by astronauts since 2000 [source: NASA].

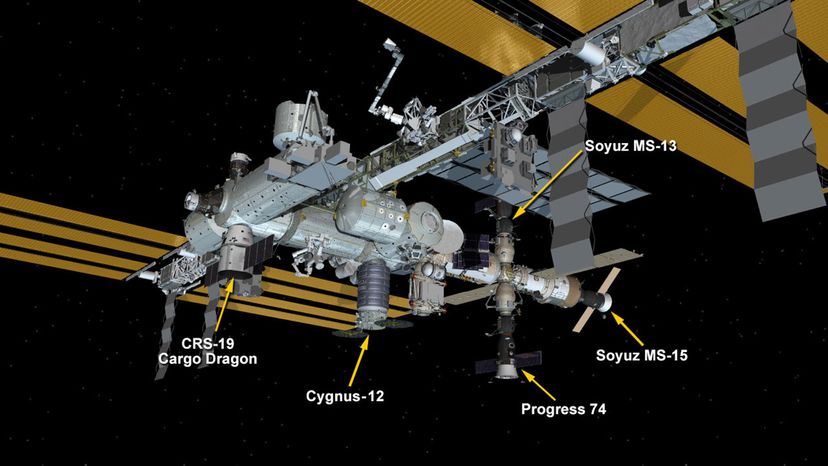

The ISS contains a vast array of interconnected airlocks, docking ports and pressurized modules [source: NASA]. As of April 2022, a grand total of 248 spacewalks have been conducted at the station [source: NASA].

The ISS will continue to receive funding until at least 2030, as announced by the Biden administration Dec. 31, 2021. So far, this stellar project has cost participating nations more than $100 billion — and NASA spends $3 to $4 billion on it per year [source: Greenfieldboyce].

In this article, we'll look at the parts of the ISS, how it maintains a permanent environment for humans in space, how it's powered, what it's like to live and work on the ISS, and how, exactly, we'll use the ISS. First, we'll start with its parts and assembly.

Advertisement