If planets can have moons, could those moons have moons of their own? After all, some moons in our solar system — Jupiter's moon Ganymede and Saturn's moon Titan — are actually bigger than Mercury, the smallest of the eight planets recognized by the International Astronomical Union.

But astronomers have yet to discover a moonmoon, i.e. a moon either orbiting around a moon in our solar system or outside it. (For that matter, they only recently discovered what might be the first exomoon, a Neptune-sized object that appears to be orbiting a massive exoplanet called Kepler-1625b.) Could moonmoons even be a thing? Or would the powerful gravitational field of the planet take over and either pull them out of their moon orbit or cause their destruction?

Advertisement

In a draft version of a scientific paper posted on the arXiv pre-print server, Carnegie Observatories astronomer Juna A. Kollmeier and Sean N. Raymond of the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux in France calculate that moonmoons — or submoons, as they call them — would indeed be possible, but only given certain narrow conditions.

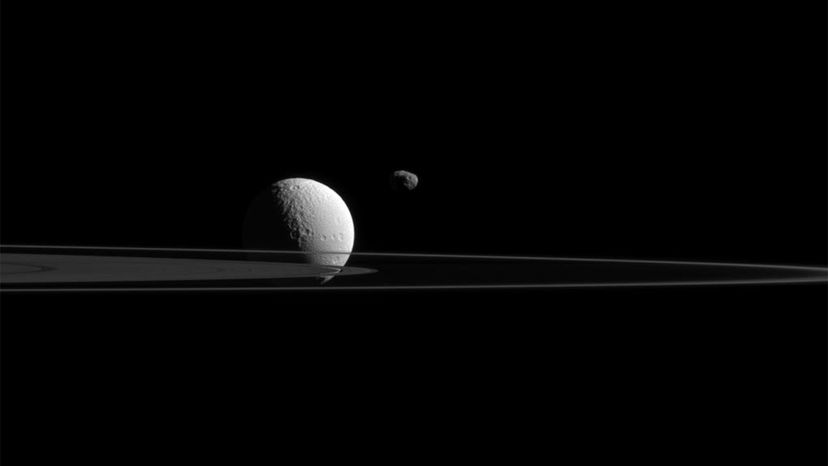

Moonmoons of 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) or more in diameter could only exist around moons that are at least 100 times that size and traveling in wide-separation orbits around their planets, the researchers determined. They found that four moons in our solar system — Saturn's moons Titan and Iapetus, Jupiter's satellite Callisto, and Earth's moon — would fit the criteria, along with the newly discovered possible exomoon orbiting Kepler-1625b.

But, as Raymond said in the October 10, 2018 issue of NewScientist, even though moonmoons are possible, a hunk of rock would have to be kicked off into space at the right speed so that it would orbit around that moon, rather than the planet or a nearby star. Also, if a moon moves around in the course of its evolution, as Earth's moon has done, the moonmoon probably wouldn't stick with it. That may be why we haven't actually found any moonmoons so far.

Advertisement